You’d think by now the collective media would have “Kansas fatigue” when it comes to reporting on the never ending tale of education funding here in the Sunflower State. We all know how the story goes by now: the big, bad governor/legislature slashes school funding as a step toward defunding public education with unthinkable consequences to the most vulnerable school children, thwarted by the heroic deeds of the state’s Supreme Court only to see the big/bad governor/legislature rise again. You know, it’s like watching Dudley Do-Right.

Apparently, reports of fatigue have been greatly exaggerated.

The latest version of this “scary tale” comes courtesy of a podcast (referred to as an “episode”) entitled “Revolution in a Cornfield” from a group called Life of the Law. Never heard of them? Neither had I. What is this “episode?” Think of it as an NPR’s “All Things Considered” wannabe. A host with a soft, soothing yet authoritative voice, topical subject matter, sympathetic characters, a distinct point of view with a cast of supporting interviewees, perfunctory opposing views, and of course distorted and sometimes outright fallacious data to support their agenda. Oh, yeah, and lots of soft background music (Cue that harp!) with enough ambient noise to give the setting an undeniable sense of authenticity.

Put all that in your Vitamix and, voila!, you’ve whipped up a Life of the Law episode.

“Revolution in a Cornfield” is presented and narrated by Ashley Cleek, who begins the episode at Mark Twain elementary in the Kansas City (USD 500) school district. The principal of Mark Twain, Katie Egidy, paints a dismal picture of larger class sizes and fewer services to deal with students in poverty and those with limited English ability because she says “there isn’t enough money.”

Apparently, neither Egidy nor Cleek is aware that the district reported operating reserves in excess of $60 million in 2015, which is over 18% of their total operating budget and 50% more than when Edigy started 8 years ago. And I guess they aren’t aware that it was the decision of the superintendent and the school board not to part with the money that could have put additional teachers at Mark Twain.

Cleek then reveals a compassionate side of Edigy that is simultaneously heart-wrenching and troubling. The principal speaks tearfully of Denis, a student new to the U.S. from Burma, who is needy in virtually all economic aspects. It is clear she wants to be involved in providing for many of Denis’s needs outside school.

My little Denis. He needs everything.

As a former teacher and one who has had many “Denis’s” over the years, I am empathetic toward Denis and understand Edigy’s concerns. However, we cannot lose sight of why we are there. Not to belabor the obvious, but schools are there to educate, and not just one or two, but ALL students. We can’t focus all our attention on just a few and forsake the rest. The best teachers and administrators I know are firmly grounded in that approach.

Cleek moves next to USD 500 superintendent Cynthia Lane who somehow makes a rather curious connection among education funding, student neediness, and, of all things…snow days. Lane says:

For me, there’s another decision that really makes it more difficult to close schools — it’s the fact that many of our children won’t have food, the day that the school is closed, they count on coming to school for their meals.

Lane is tugging at our heartstrings to make a case for more school funding. Although Ms. Cleek may not completely understand, Lane knows fully that she is making a flawed appeal for more funding. She wants us to believe that students like Denis are so completely dependent on the public school system for basic needs such as food that it clouds her judgment concerning the decision to call a snow day. Closing schools due to weather is a safety issue. Would she really put the welfare of 20,000 students in jeopardy because she’s afraid a few of them might not get lunch? But that aside, how would increased school funding feed children at home when school is closed due to weather?

But the superintendent doesn’t stop there. Lane claims the district lost hundreds of jobs due to funding cuts and implies they haven’t returned. Specifically she asserts “400 people lost their jobs, 130 were classroom teachers.” According to KSDE data (reported by USD 500) in 2008-009 the Kansas City school district had 1,514 teachers. The following year that number was reduced by 64. However, since the recession, the number of teachers has climbed to 1,732 which is a 14% increase over pre-recession highs. Putting it in a different perspective, pupils per-teacher has decreased from 12.2 to 11.8. Perhaps a little fact-checking might have been in order.

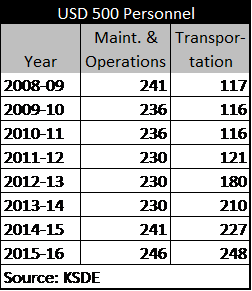

Lane still wasn’t done. She says there were other personnel reductions as well, including “fewer bus drivers, custodians were cut.” Really. The adjoining table paints a much different picture.

And then there’s administration. USD 500 spends nearly $1,300 per pupil on administrative costs, which is fourth highest among the 25 biggest districts in the state. They even have a Chief of Staff who makes $133,000 per year. That amount would more than pay for a couple teachers at a needy school like Mark Twain.

As a result of the recession, Cleek says: “Lane’s district lost 11 million (dollars).” What she fails to mention is the increase in funding since that time. According to KSDE, state aid to USD 500 in 2014-15 was $56 million higher than the 2009-10 level.

Of course, any discussion of the state of Kansas education funding would be incomplete without addressing lawsuits. Enter Alan Rupe, a lawyer representing districts who have brought litigation. Not surprising, Rupe makes an erroneous connection between spending and outcomes, even making the ridiculous statement that after the Montoy decision “the gulf between poor students and wealthy students started to narrow.” Time and time again KPI has shown that the performance “gulf” based on income has actually increased over time, regardless of funding levels.

For a lawyer intimately involved in the lawsuit, Rupe doesn’t seem to have much of a grasp on money spent on at-risk students. According to Rupe,

The shift has been from a consideration from what does it costs to educate a kid who is at risk and has special needs — to what do I want to spend on kids that are at risk and have special needs?

Perhaps he needs reminding that at-risk funding more than tripled over the last decade to nearly $400 million a year (directly as a result of their lawsuit, no less), with no results to show for it.

Rupe does, however, make one good point, and that’s his take on how the legislature is reacting to the Supreme Court decisions. He says, “to keep the judges from being able to decide the case, they want to appoint the judges in a different way.” It seems the legislature does spend a disproportionate share of their collective time trying to please the Supreme Court when it comes to education funding. Doing so makes them appear a subordinate branch of government. When the legislature caved to the Supreme Court’s Montoy decision allowing the court to dictate how much the legislature had to cough up a decade ago, they effectively became the lesser of the two branches. The legislature now faces a similar situation regarding the latest Supreme Court decision in Gannon. Allowing itself play a subservient role to the Supreme Court regarding education funding jeopardizes the fundamental concept of separation of powers. It’s the legislative body that has the power of the purse.

In its latest decision, the court attempts to expand its influence over education by threatening to shut down schools if the legislature doesn’t comply with their wishes. Mike O’Neal, president and CEO of the Kansas Chamber of Commerce, wrote this excellent piece detailing how the court has clearly overstepped its bounds, including the threat of school closure.

The term “constitutional crisis” is one that is both overused and misused, but in this case it applies. If the legislature continues to allow the Supreme Court to decide how much is spent on education, what’s next? Roads and Highways? Medicaid? Tourism? Maybe the court should do the entire state budget?

Without a dramatic change in this balance of constitutional power, the carousel of lawsuits, which is the basis for reports like this one, will continue its inexorable loop. The legislature should reassert itself as a co-equal branch of government, instead of tinkering with the composition of the court.

The podcast concludes with an interview that is simultaneously poignant and ironic. Marie Freeman, who appears to not only be a great-grandmother, but a great great-grandmother is actively involved in the education of her great-grandchildren. Her great-grandson is a student at USD 500’s Northwest Middle School. According to Ms. Cleek,

Freeman’s seen the (funding) cuts. The old uniforms. The firing of custodians, teaching aids and teachers.

What makes it ironic is that Northwest Middle School received a multi-million dollar federal School Improvement Grant (SIG), pursuant to the old No Child Left Behind law in 2010. The concept of the SIG was to inject significant amounts of money into failing schools to increase student performance. In Northwest’s case, it didn’t work. Four-point-seven-seven million dollars later, both reading and math scores are lower. Read here for more detailed information.

The poignant part is Marie Freeman’s statement about kids’ education and funding. She, too, complains of less money, but speaking as a grandmother would, she says

The students, to me, they look like a dollar sign these days. Cause you get so much money per child. But you got to look at the kids beyond a dollar sign.

Amen to that.

Unfortunately, to people like Ms. Cleek and groups like the Life of the Law, that seems to be all they understand: that the quality of education is strictly a function of dollars and cents. She couldn’t even grasp that public education is a government function. Her lack of understanding shows in this exchange with KPI president Dave Trabert:

Trabert: When government doesn’t get as much as it wants, that’s a cut (to them).

Cleek: Well, it’s a school, so it’s not government.

Yes, not only did she say that, she didn’t even bother to edit it out.

The fact that she chose Mark Twain Elementary as her focus, begs for a Mark Twain quote as a closing. This says it all for those like Ashley Cleek and scores of others who just don’t get it:

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.