This recent post detailed the latest usurpation of local control by the federal government. It concluded by posing this question: Could Kansas, in an attempt to regain local control, tell the feds we will no longer participate in their programs and that they can keep their money?

The purpose here is to investigate the potential impact of pursuing such a course of action.

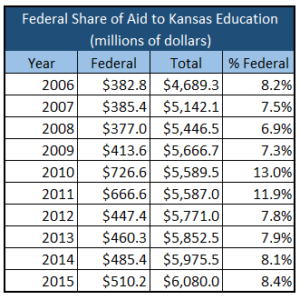

In 2015 total federal support was just over $510 million which is 8.4% of all funding. The percentage of total dollars to education that comes from Washington has consistently been in the 7% to 8% range over the last decade. During that time frame it has never exceeded 10%, save for 2010 and 2011, which were anomalies because federal stimulus dollars were supplements during the recession.

In 2015 total federal support was just over $510 million which is 8.4% of all funding. The percentage of total dollars to education that comes from Washington has consistently been in the 7% to 8% range over the last decade. During that time frame it has never exceeded 10%, save for 2010 and 2011, which were anomalies because federal stimulus dollars were supplements during the recession.

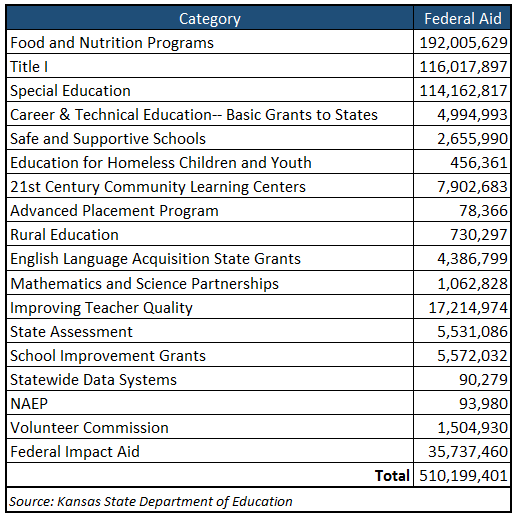

What follows is a comprehensive overview of all the programs and funding to education that came from Washington in 2014-15. This information is a summary of a presentation made by KSDE’s Dale Dennis to the House Education Committee that I happened to be attending during the 2016 session. It doesn’t appear to be available in this form on the KSDE website. The following table itemizes the 18 categories of federal programs and grants that provide the $510 million to the state, districts and schools, and in some cases non-school entities.

Clearly, three categories dominate federal support. Food and nutrition programs, Title I and special education account for over $422 million of the $510 million in federal aid. That’s nearly 83% of all federal participation.

The following is a summary of those federal programs/grants, along with the 2014-15 dollar amounts and state matching funds/support where applicable.

Food and Nutrition Programs ($192,005,629; state match – $2,510,429).This category is much more than just school lunches. There are 11 separate food programs in which Kansas receives federal dollars:

Food and Nutrition Programs ($192,005,629; state match – $2,510,429).This category is much more than just school lunches. There are 11 separate food programs in which Kansas receives federal dollars:

- School Breakfast Program

- National School Lunch Program

- Special Milk Program for Children

- Child and Adult Care Food Program

- Summer Food Service Program for Children

- State Administrative Expenses for Child Nutrition

- Team Nutrition Grants

- Farm to School Grant Program

- Child Nutrition Discretionary Grants Limited Availability

- Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program

- Cooperative Agreements to Promote Adolescent Health

Title I ($116,017,897). Title I dollars are supposed to be targeted toward economically disadvantaged students. In practical terms, it’s the federal version of at-risk funds.

Special Education ($114,162,817; state match – states must maintain previous year dollar amount). The dollars are allocated to assist the state and school districts to comply with requirements of the law for children with disabilities.

Career and Technical Education ($4,994,993; state match – $392,650). Start-up costs for approved courses/programs – cannot be used for existing programs.

Safe and Supportive Schools ($2,655,990). Money for violence and drug prevention, other prevention programs. This is a grant that expires in June 2016.

Education for Homeless Children and Youth ($456,361). Beyond the classroom support for things like professional development to staff, after school programs, tutoring and more.

21st Century Community Learning Centers ($7,902,683). Competitive grants that provide money to help establish collaborative after school programs between schools and community organizations like Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs and others.

Advanced Placement Program ($78,366). Funds to pay for students’ fees for exams taken at the end of an AP course.

Rural Education ($730,297). Funds to address the unique needs of rural districts like teacher recruitment and retention, educational technology and others.

English Language Acquisition State Grants ($4,386,799). Funds are for helping teachers meet ESOL licensure requirements and program materials to those in ESOL programs.

Mathematics and Science Partnerships ($1,062,828). A three-year competitive grant in which the money goes to high need school districts that partner with non-profits and businesses to increase the achievement of students in math and science.

Improving Teacher Quality ($17,214,974). This is a formula- driven allocation for all districts for professional development, mentoring, teacher evaluation, salaries to reduce class size, and others.

State Assessment ($5,531,086). Funds to assist states in the provision of state assessments.

School Improvement Grants ($5,572,032). Competitive grants directed to persistently low achieving schools like Priority and Focus schools.

Statewide Data Systems ($90,279). This was a competitive grant that ended in June 2015.

NAEP ($93,980). This pays the salary of one KSDE employee who coordinates with NAEP on their assessments.

Volunteer Commission ($1,504,930; state match – $145,000). This is funding to support national service organizations like AmeriCorps, Senior Corps, and Learn and Serve America.

Federal Impact Aid ($35,737,460). These are funds paid to districts that have federal lands that were taken off property tax rolls like Fort Riley and Fort Leavenworth. (Please note: the 2014-15 allocation, according to Mr. Dennis, was particularly high because new schools were built on Fort Riley and Fort Leavenworth.)

Now addressing the fundamental question: What if Kansas told the federal government thanks but no thanks? First of all, this is not an endorsement on either side of the question. Nor is this meant to make any assumptions about the legalities that might preclude withdrawing from any particular federal program. Furthermore, given the litigious world in which we live, it is naïve to think that an attempt to severe financial ties with the feds would not be challenged with a bevy of lawsuits from parents, advocacy groups, school districts and likely the federal government itself. Any action to reject federal funding would most likely end up in the courts. The latest federal intervention, the transgender bathroom directive by the Department of Education and the Department of Justice, has spawned an eleven-state lawsuit. (Kansas is not part of this suit, but is involved in a similar one.) But putting all that aside for the sake of discussion, would Kansas really “lose” over half a billion dollars that would have to be funded by Kansas taxpayers? That is unlikely because of compliance costs and other savings that could be realized and thus reduce the net loss.

We’ll start with the biggest program, food and nutrition. Since the food programs are largely reimbursement-based, it is at least conceivable Kansas public schools could still provide a food and nutrition program sans the federal government. Would that result in the loss of $192 million? Most likely, not. Because along with the money comes over 260 pages of guidelines, as published by KSDE which undoubtedly lead to unreported compliance costs. The amount of money districts would actually lose would depend on how many of the 11 programs the state and/or districts would continue in the absence of federal “carrots” and how much more efficient the districts could run their food programs without being under the thumb of federal regulations. Legislative Post Audit studies have shown that some districts could save money on providing food. Regional food service providers could lower the cost. And one need look no further than lunchroom trash cans to see how much food that is provided in the name of nutrition is thrown out by the kids. The actual cost to the state would depend on how Kansas schools would replace the existing program.

We’ll start with the biggest program, food and nutrition. Since the food programs are largely reimbursement-based, it is at least conceivable Kansas public schools could still provide a food and nutrition program sans the federal government. Would that result in the loss of $192 million? Most likely, not. Because along with the money comes over 260 pages of guidelines, as published by KSDE which undoubtedly lead to unreported compliance costs. The amount of money districts would actually lose would depend on how many of the 11 programs the state and/or districts would continue in the absence of federal “carrots” and how much more efficient the districts could run their food programs without being under the thumb of federal regulations. Legislative Post Audit studies have shown that some districts could save money on providing food. Regional food service providers could lower the cost. And one need look no further than lunchroom trash cans to see how much food that is provided in the name of nutrition is thrown out by the kids. The actual cost to the state would depend on how Kansas schools would replace the existing program.

Title I is a different animal. It is formula driven and is essentially an entitlement program. Title I dollars are allocated on a school-by-school, not student-by-student basis. As a result, only about half of the more than 1,300 schools state-wide qualify as Title I schools. The feds have a “supplement-not-supplant” requirement, which means Title I funds are technically there to enhance local efforts to serve economically disadvantaged students not replace existing efforts. An elimination of the program would a) only impact half the schools in the state and b) force the eligible districts to justify replacing the federal dollars. In other words, it is unlikely a dollar-for-dollar replacement of Title I money would happen if the program went away.

Title I is a different animal. It is formula driven and is essentially an entitlement program. Title I dollars are allocated on a school-by-school, not student-by-student basis. As a result, only about half of the more than 1,300 schools state-wide qualify as Title I schools. The feds have a “supplement-not-supplant” requirement, which means Title I funds are technically there to enhance local efforts to serve economically disadvantaged students not replace existing efforts. An elimination of the program would a) only impact half the schools in the state and b) force the eligible districts to justify replacing the federal dollars. In other words, it is unlikely a dollar-for-dollar replacement of Title I money would happen if the program went away.

Special education funding brings with it a complex interconnection among state, local and federal dollars. Because of the legal rights of special education families and the myriad of laws at both the state and federal levels, those laws would have to be analyzed to assess the feasibility of forsaking federal dollars.

Special education funding brings with it a complex interconnection among state, local and federal dollars. Because of the legal rights of special education families and the myriad of laws at both the state and federal levels, those laws would have to be analyzed to assess the feasibility of forsaking federal dollars.

The remaining fifteen categories can be put into these groups: grants that come and go; programs that have very small dollar amounts which, if warranted, could easily be absorbed into state or local aid; money that goes to other organizations in the name of education; or programs that may not be warranted in the first place.

Another consideration not yet mentioned are the compliance costs that are inexorably attached with administering federal dollars. Those are the costs incurred by the state and districts in order to fulfill federal requirements attached with accepting money. Although there is no readily available accounting of those costs, they are real. In addition to hard dollars, there are opportunity costs that are incurred when teachers spend time on those programs, time taken away from attending to student needs. Title I is a good example. As a former Title I employee, I recall all the burdensome requirements that the feds and/or the state put on us. Those requirements included things like tracking students, attending meetings, making purchases, maintaining inventory among others, all costing a teacher’s most precious commodity: time.

In conclusion, the call here is for the legislature to fully investigate the issue of the potential impact of forgoing federal education dollars. This is clearly an issue of maintaining local control in the face of federal intervention – intervention which reached critical mass during No Child Left Behind and is now at a breaking point regarding the threats that accompany the transgender bathroom issue. It’s not going away and it’s time the legislature start responding. Ordering financial audits to determine the net costs of a policy change along with legal opinions would provide the legislature with information needed to determine whether severing ties with the federal government regarding education is something they would choose to pursue. And with the latest overreach by the Kansas Supreme Court to dictate education funding, if ever there was a time for the legislature to exert their authority, now is that time.