On the first of February, the Kansas Department of Revenue announced that January tax revenue estimates had come in $64 million – or 6.5% – below the estimate for the month. Governor Laura Kelly was quick to turn the issue into one about the current flat tax debate, proclaiming that the report was a reminder that “tax cuts must be done in a fiscally responsible way.” In other words, it’s the same “my $1.1 billion tax plan is responsible; anything else is Back to Brownback” rhetoric she’s used over the last year.

Let’s break down what the revenue numbers mean, and why they aren’t the “impending doom” some commentators have made them out to be.

The revenue estimates are created by the Consensus Revenue Estimating Group (CREG). The group meets in November and April of each year to constantly revise its estimates. Given that Kansas had a 27-month period from July 2020 to October 2022 of continually exceeding its CREG revenue estimates by hundreds of millions of dollars above actuals, it makes sense that many would assume the CREG would continue to overshoot.

This misestimation continues the historical inaccuracy of the revenue estimates, particularly those of the Consensus Revenue Estimating Group. For instance, the CREG originally thought that FY 2022 would bring in $5.8 billion for the state, but later upped the estimate to $7.6 billion; the next year, the original estimate of $7.8 billion had to again be upped to $9.2 billion halfway through the year. You read that correctly. Those are billion-dollar-plus differences. We’re not talking about rounding errors. Overestimations in the mid-2010s caused inaccurate revenue predictions that contributed to the Brownback era tax reform “mess.” This continued miscalculation certainly contributes to boom-and-bust budgeting issues regardless of who occupies the Governor’s Mansion.

On one hand, the Group’s November 2023 update slightly decreased its FY 2024 receipts by $67.7 million – a 0.6% decrease. As of January 2024, the state is currently $111 million below that estimate, which is 1.1%. But on the other, the state’s revenue has drastically increased over the last three years, and it’s hard to believe that a small shortfall will overcome the $4.5 billion stockpile of cash the state has in its coffers.

The current cumulative total receipts of FY 2024 are still 5.6% higher than the January update for FY 2023. However, tax collections are down by 1.7% ($94 million) compared to then.

Wariness about the slightly lower tax revenues is wise. But political maneuvering to use it to shut down attempts at tax reform is overblown. The Kansas Legislative Research Department estimated that Kansas would still have a $4.5 billion surplus four years after a flat tax if one had passed during the 2023 legislative session.

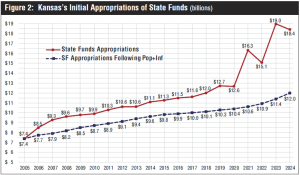

If Kansas’s budget was a coin, revenue is just one side; spending is the other component. And like revenue, its drastically increased in recent years. From FY 2020 and FY 2023, Kansas’s State Fund Appropriations (total spending without federal funds) increased from $12.6 billion to $19 billion. For comparison, if the budget had only grown at the rate of population growth plus inflation since 2005, it would have been $7.6 billion lower in FY 2023. The below graph from the Responsible Kansas Budget demonstrates this.

There is always room in the budget – especially one that elected officials have elected to grow by $6 billion over three years – to eliminate waste and operate more efficiently. In 2021, Kansas spent $4,932 per resident, while states without an income tax on average spent $2,836 while providing the same basket of goods and services.

After several years of inflation and a sluggish economy, Kansas families deserve tax relief—and not just one-time fig leaves but actual lower rates–which is well in reach with the state’s current surpluses. Economic troubles are bound to arise in the future: that’s part of the cyclic nature of the economy. But through responsible budgeting, Kansas can weather the storm like the two dozen other states that enacted tax reform since 2012.