The underlying theme of a presentation on cash reserves at the April State School Board meeting was that districts have appropriate reserves from the Kansas Department of Education’s system-focused perspective. But one might have a different conclusion examining cash reserves from a student-focused perspective.

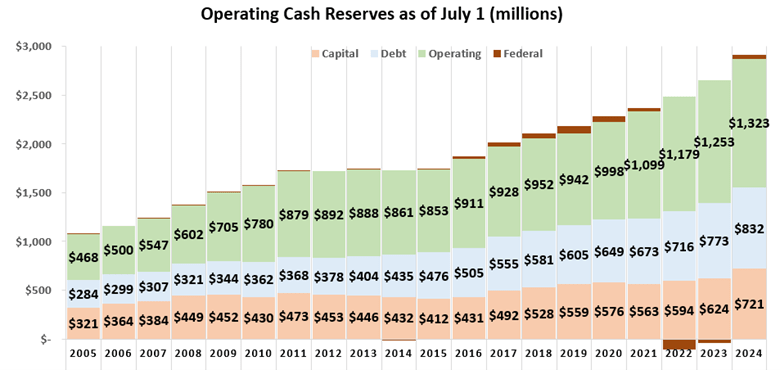

KSDE finance chief Frank Harwood said school districts had $854 million in operating funds on July 1, 2024, which he defined as “funds that can be used for general or specific operational purposes.” However, the real total in standard accounting terms is $1.323 billion, as shown below.

The difference is a group of funds Harwood described as ‘levied funds;’ those funds do include property taxes levied on taxpayers, but the money is still used for current district operations and should be counted accordingly. (In accounting terms, current spending excludes long-term spending on debt payments and capital outlay.)

Districts also had $832 million set aside for debt payments, $721 million for Capital Outlay, and $41 million in Federal reserves. Balances by category and fund balance for each district is at KansasOpenGov.org.

Think of cash reserves like your checkbook balance; if it is higher at the end of the year compared to the beginning, you didn’t spend everything you deposited. At the beginning of 2005, districts held $468 million in operating reserves; since then, districts have taken in about $850 million more than they spent, most of which comes from state and local taxes.

Harwood said legislative studies recommend having about 15% of expenses in reserve, and he calculated that districts have 15.7% held back based on having $854 million in operating reserves divided by $5.8 billion in operating revenues. The math works out to 14.7%, by the way; further, operating reserve ratios are calculated against spending, not revenue. The reserve ratio measures the ability to cover expenditures, so revenue is not a reasonable basis for measurement.

School districts had $1.253 billion in operating reserves at the beginning of the 2024 school year. Operating expenses were $6.466 billion (total spending less capital outlay, debt payments, federal spending, and KPERS, as the first three are not part of operating reserves and districts have no out-of-pocket expense for KPERS). That makes the average operating reserve 19.4%, and far more than districts need.

Studies often recommend higher reserve ratios for government entities for several reasons. Many are conducted or sponsored by government entities and have a built-in bias. Also, unseen consequences are rarely considered. In this case, the cost of having higher reserves is that less money is available to educate students.

Government reserve ratio recommendations also don’t consider the likelihood of significant revenue declines, which is minimal for Kansas school districts. Even during the depths of the Great Recession 15 years ago, per-student funding declined just 3% over two years.

Many districts regularly operate with lower reserves

Kansas Policy Institute first exposed the growth in cash reserves in 2011; previously, KSDE only published a few fund balances. That is an important frame of reference because school districts did not previously complain about not having adequate reserves, and education officials are not bashful about wanting more money, so it’s reasonable to believe that operating reserves were not an issue.

The average operating ratio for the 2006 school year was 12.3%, and 170 districts had less than a 12% reserve. That alone demonstrates that 10% is a realistic target. There are still 59 districts with less than 12% in reserve, showing that some districts do a much better job managing cash flow.

For perspective, local school boards could free up more than $500 million by returning to their 2006 ratios.

Local school boards could collectively draw hundreds of millions from reserves to improve student outcomes and still have adequate cash balances.

Special education reserves

Harwood said districts needed “at least 25% to 30%” in special education reserves at the beginning of the year because the first special education aid payment arrives in October.

The October payment reference is accurate, but districts don’t need money in the Special Education fund to spend on it for that purpose. According to an email received last year from KSDE, a district can transfer money from another fund to pay the bills; cash must exist somewhere, but it doesn’t have to be in the Special Education fund at the beginning of the year.

School district records also show districts don’t need large Special Education reserves at the beginning of the year. Nine districts had zero Special Education reserves at the beginning of the 2024 school year, and 31 more had less than 10% in reserve. Again, good cash management means more money is available to educate students.

Conclusion

A lot more can be said about cash reserve guidance, but hopefully, the examples here are sufficient to make two points: (1) hundreds of millions of dollars could be put to better use, and (2) state and local school board members need better training.

KPI and our affiliate, the Kansas School Board Resource Center, can provide the training upon request.