The Supreme Court held oral arguments on May 9 prior to their upcoming seventh Gannon opinion. As has been the case throughout the nearly decade-long Gannon saga, each oral argument phase brings at least one new variable that makes predicting what the Court might decide a fool’s errand. This go-around there were two such variables:

1. The discussion of inflation dominated the session. In fact, the word inflation (or inflate) was spoken no less than 71 times in the roughly one-hour session. (Yes, I counted them.) And that doesn’t include the number of references to the Consumer Price Index, another indicator of inflation.

2. Seemingly out of nowhere, Justice Biles – who once again took over the discussion – questioned whether the baseline dollar figure that was ordered by the Court in Montoy in 2005 represented the floor amount for constitutionality.

The State’s case

State Solicitor Toby Crouse argued that the state has complied with the Court’s directive in Gannon VI – particularly the calculations outlined on pages 25 and 26 in the opinion. He noted that the Republican dominated Legislature passed a bi-partisan bill that was signed by a Democrat governor. In addition, the increase in state aid in the new legislation (SB 16) was calculated by KSDE and endorsed by the state board of education. In other words, the state speaks with unanimity that the approximately $90 million in additional funding will bring the state into constitutional compliance.

The plaintiff’s case

The attorney for the plaintiff, Alan Rupe, argues that the new legislation incorrectly calculated inflation, therefore the state is still approximately $270 million short of constitutionality.

The discussion

Inflation

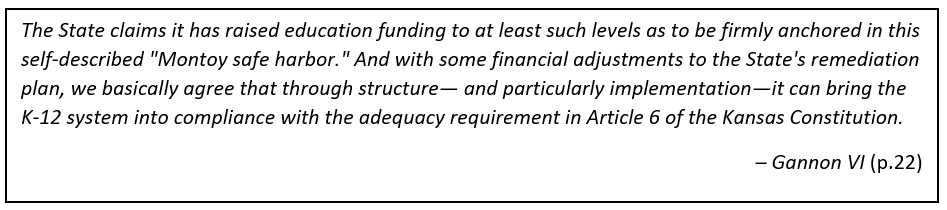

To understand how inflation has now taken center stage in Gannon, a review of the last Gannon opinion is necessary. The Court claimed on page 25 of the opinion that the Legislature failed to calculate inflation for 2018 and 2019 and “inflation adjustments to the principal should be made for those two years.” To address that concern, KSDE calculated the inflation-induced shortfall, thus $90 million more was allocated in SB 16. The main point of contention throughout the arguments was whether the state correctly applied a rate of inflation and secondarily, whether funding would reach the so-called “Montoy safe harbor” level by 2023.

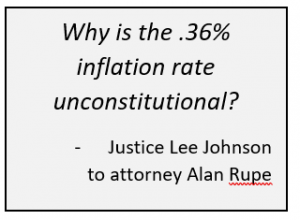

The obtrusiveness of the Court into the legislative process has led the justices down a rabbit hole. The Gannon sessions have devolved to the point that the constitutionality of the education funding mechanism hinges on which rate of inflation is employed. That’s where much of the back and forth between the justices and the lawyers was spent during the Gannon VII arguments. Is the “proper” inflation rate .36% or 1.44%? Where in the constitution, the very document the Court is supposed to be interpreting, is any reference to inflation? There isn’t any, which made the proceedings resemble a legislative committee meeting, not a Supreme Court hearing.

The obtrusiveness of the Court into the legislative process has led the justices down a rabbit hole. The Gannon sessions have devolved to the point that the constitutionality of the education funding mechanism hinges on which rate of inflation is employed. That’s where much of the back and forth between the justices and the lawyers was spent during the Gannon VII arguments. Is the “proper” inflation rate .36% or 1.44%? Where in the constitution, the very document the Court is supposed to be interpreting, is any reference to inflation? There isn’t any, which made the proceedings resemble a legislative committee meeting, not a Supreme Court hearing.

Montoy redux?

Simply put, in Gannon VI the Court opined that “Montoy safe harbor,” which is essentially an extension of the Court-ordered education funding back in 2005 had the Legislature not been forced to reduce funding due to the Great Recession, would be OK. However, Justice Biles pointed out that no Court has ever said that Montoy was the floor amount to achieve constitutionality.

Simply put, in Gannon VI the Court opined that “Montoy safe harbor,” which is essentially an extension of the Court-ordered education funding back in 2005 had the Legislature not been forced to reduce funding due to the Great Recession, would be OK. However, Justice Biles pointed out that no Court has ever said that Montoy was the floor amount to achieve constitutionality.

The absurdity of anything Montoy-related is yet another example of the Kansas Supreme Court ignoring precedent, including its own ruling. In March 2014, in Gannon I they sent the case back to Shawnee County district court, saying the lower court used the wrong test in finding funding to be inadequate. The Supreme Court issued a new test of adequacy (funding must be reasonably calculated so students can achieve certain academic outcomes) but now they are back to basing their decisions on Montoy funding levels – even though nothing in that case was calculated to achieve any sort of academic outcomes.

So now what we have is a nearly decade-old case in Gannon which has been perpetuated by a myth. A myth that the state, by not funding education at the projected level established in Montoy, was out of constitutional compliance when it was never established in the first place that Montoy represented a constitutional solution to structure and implementation of the educational funding mechanism.

Do you see what happens when the Court usurps legislative authority?

And so it goes. The Court will issue its seventh Gannon opinion before the end of June. Absent a specific prediction, it is unlikely the Court will dismiss the case. Justice Biles who has little, if any, faith in the legislative process said this to Mr. Crouse:

“I’ve gotta tell you, I don’t have a lot of sympathy for the idea of dismissing this lawsuit…If we were to dismiss this lawsuit now and next year the legislature went back and put in that block grant program that we’ve already said is structurally unconstitutional…the law of this case would prevent that law from being implemented…If we dismiss it (the plaintiffs) got to go back to the district court…and we’re off to the races…when what the Legislature did is something we’ve already said they can’t do. And that seems to be wrong…That’s my problem. How are you going to get me past that?”

“I’ve gotta tell you, I don’t have a lot of sympathy for the idea of dismissing this lawsuit…If we were to dismiss this lawsuit now and next year the legislature went back and put in that block grant program that we’ve already said is structurally unconstitutional…the law of this case would prevent that law from being implemented…If we dismiss it (the plaintiffs) got to go back to the district court…and we’re off to the races…when what the Legislature did is something we’ve already said they can’t do. And that seems to be wrong…That’s my problem. How are you going to get me past that?”

Although the question was posed to Mr. Crouse, perhaps I can answer that. Any structural change like a block grant approach would have to have the signature of Governor Kelly. That’s not going to happen, and Justice Biles knows it. His concern is vastly overstated and sounds more like an excuse for maintaining a grip on education funding. It should be noted that Justice Biles was an attorney for the state board of education and argued on their behalf during the Montoy case.

Who knows? Maybe Gannon VII will be the end of it. Hope springs eternal. Justice Rosen, who sounded exasperated and looked like he is having a case of Gannon fatigue, asked Mr. Rupe, “When does it end?…Is there ever crossing the finish line or are you going to be back here 3-4 years down the road making the same argument?”

The answer is actually quite simple. It ends when the Kansas Supreme Court gets out of the Legislature’s business.