In a recent response to the precipitous decline in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores, the Kansas Association of School Boards (KASB) has spun the results to:

-> minimize the importance of NAEP,

-> identify spurious excuses, and

-> ultimately point the finger of blame at…you guessed it, not enough money.

KASB trivialized NAEP to make the results seem both insignificant and suspect by stating that NAEP “tests a small sample of students,” implying that the scores don’t mean much and that the results can’t actually be extrapolated to the general population. Despite how KASB portrays NAEP, KSDE calls it the “gold standard” of assessments.

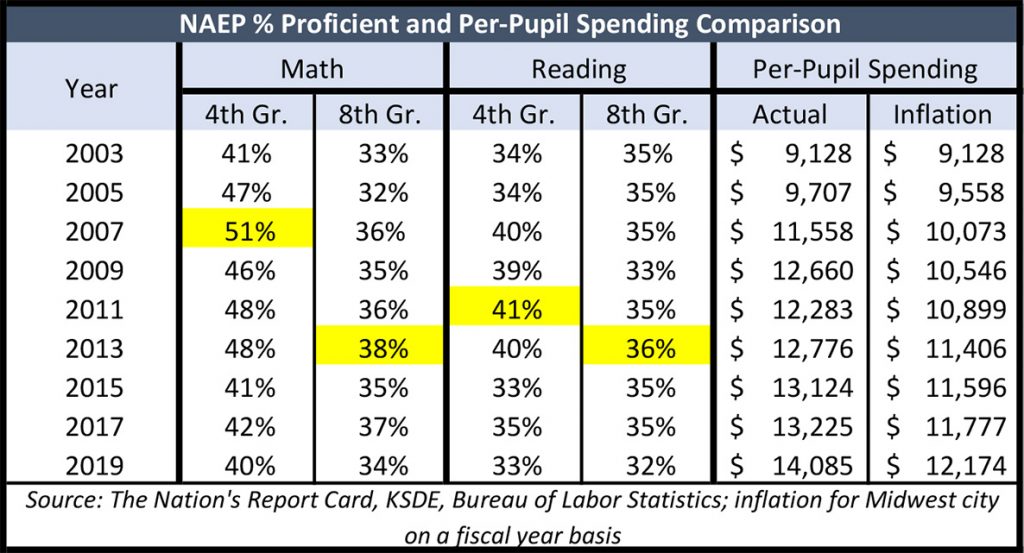

The report also plays fast and loose with trends in NAEP data, including making a patently false statement. The claim is “Kansas results peaked around 2009 and 2011 and have generally declined since. Translated: Scores were highest when there was more money pursuant to Montoy and they declined because funding went down after the Great Recession. The only problem with their printed words is that is simply not true. As the table indicates, there has been no ‘peak periods’ in NAEP performance. To wit:

-> 4th-grade math: the scores were relatively stable from 2005 to 2013 before a sharp drop-off in 2015 that has continued in 2017 and 2019 – now below 2003 levels.

-> 4th-grade reading: the results were steady from 2007-13, scores dropped in 2015 and are now also below 2003 scores.

-> 8th-grade math: results were similar from 2007 to 2017 but now are barely above 2003 levels.

-> 8th-grade reading: scores were remarkably consistent from 2003 to 2017 but now are lowest ever.

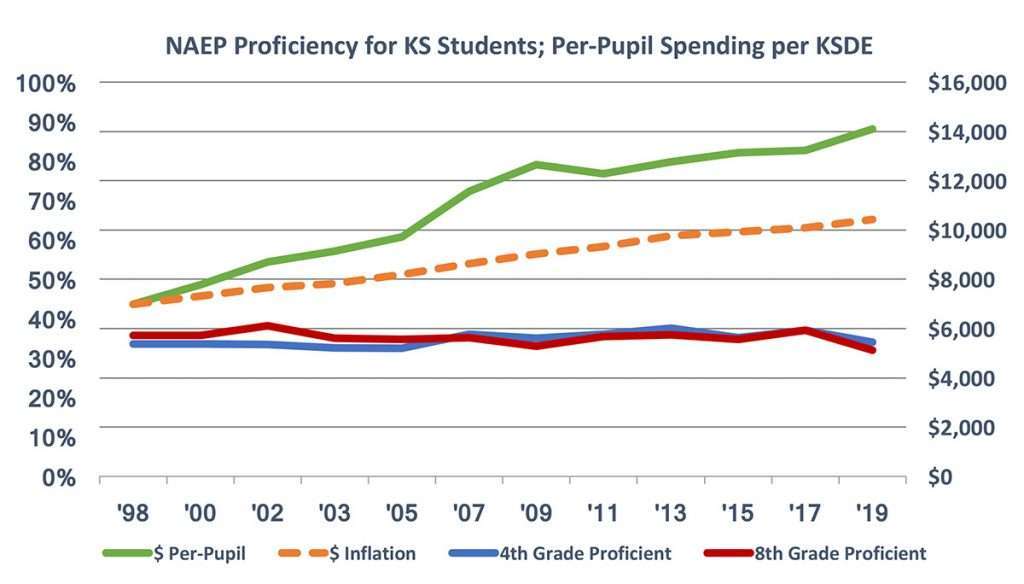

KASB and the rest of the education establishment have consistently tried to make the public believe that money is the driving force behind test scores. This remains evident in the Gannon saga and will remain so despite our present Gannon reprieve. Those lobbying for more money to public education pointed to the rise in test scores during the No Child Left Behind years after court-ordered Montoy money went into school coffers. Going back two decades as NAEP began widespread adoption, it is clear that increasing spending (green line in the chart below) does not impact student achievement. The only objective statement is that spending has far outpaced inflation and NAEP achievement is stubbornly flat.

In light of this evidence, KASB seem to be humming a different tune when it comes to the impact of court-ordered money pursuant to Gannon. Now, according to KASB, “it will take time for improvements to follow the funding.” I don’t recall hearing that argument during the Gannon trial. Maybe money really does make a difference – a difference in how excuses are formed for explaining sagging assessment results.

KASB unabashedly admits the money has been used to make up for lost time for such expenses as increasing teacher salaries – KASB is quick to point out that “educator salaries fell behind inflation” – increasing building principals, assistant principals and support staff. The report details other expenditures districts have made with the additional funding – “to stabilize and repair the challenges created during this eight-year period,” as they refer to it. There is nary a mention of targeting at-risk students, which was supposed to be the focus of the additional money. Apparently, these additional hundreds of millions of dollars shouldn’t count toward improved results because it is basically ‘make-up’ money for all those years of being “underfunded” as the education establishment likes to call it.

I watched the Gannon deliberations pretty closely over the years and I don’t recall once the plaintiff lawyers telling the Supreme Court that the schools needed more money to increase salaries or administrative staff. As I recall, the Supreme Court made its decision to force the Legislature into providing more money to education based on targeting that money to those who were not being adequately educated, to paraphrase the justices.

KASB’s report is yet another example of the disconnect between how the Supreme Court bases its decisions and how the school districts, where actual spending decisions are made, choose to spend the money. It’s time to put the onus for educating students where it belongs – with local school districts and administrators.