The Kansas Supreme Court’s June 14 ruling that school funding now meets the court’s definition of being constitutionally adequate is likely just a ‘time-out’ in school funding litigation. The decision doesn’t preclude schools from taking further legal action, either within the current Gannon litigation or with another lawsuit. And just like large funding increases in the past, this latest billion dollar funding increase will do very little to improve student achievement.

The ultimate effect of the Court’s latest decision in Gannon – its seventh so far – came as no particular surprise. It was widely anticipated that the Court would approve the Legislature’s response to the Court’s funding concerns with passage of SB 16. It is also not surprising that the Court retained jurisdiction to monitor total funding in the out years. However, the Court’s apparent abandonment of the notion that allocation of K-12 resources should be focused on those students, who the Court itself identified in Gannon IV as being underserved, is particularly disturbing. The Court has, instead, returned to a convenient – for plaintiffs attorneys if not taxpayers – focus on total funding.

This about-face on determining adequacy is ‘convenient’ for the court and school district lawyers because it has naively concluded that the failure of schools to equip under-performing students with the basic skills that will prepare them for college or career is prima facie evidence of underfunding. In reality, former Speaker of the House Mike O’Neal says, “…it’s a failure by local school boards and administrators to allocate ever-increasing funding resources in a manner reasonably calculated to bring those students up to required performance levels. Only educators can do that.”

Gannon VII doesn’t end the litigation cycle

Sam MacRoberts, litigation director and general counsel of KPI-owned Kansas Justice Institute, says, “Because Gannon VII focused solely on money instead of students, the same financial issues will undoubtedly appear again. A [school district] will file another lawsuit claiming inadequacy of the State’s funding and the Court will start the review process all over again.”

In Gannon IV, the Court noted: “Plaintiffs have shown through the evidence from trial – and through updated results on standardized testing since then – that not only is the State failing to provide approximately one-fourth of all public school K-12 students with the basic skills of both reading and math, but that is also leaving behind significant groups of harder-to-educate students.”

Mike O’Neal, who is also an attorney, says, “it is not the State that is responsible for providing students with these skills, and it is not the Legislature’s role to provide those skills. This is fundamentally a function of the education system. Accordingly, the focus is and should continue to be on how the State’s provision for finance to the schools is being allocated by the schools in a manner that is reasonably calculated to have those under-performing students meet or exceed state standards.”

Achievement low despite billions more already spent

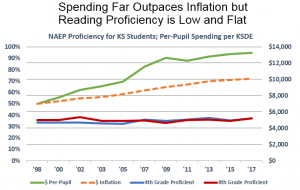

Contrary to claims by education officials, simply spending more money has not produced better achievement in Kansas or anywhere else. Reading proficiency levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) went from just 35 percent to 37 percent over the last 19 years, while spending increased far more than inflation. Kansas students’ average score on the ACT test is exactly where it was 20 years ago, and only 29 percent of all students taking the test last year were considered college-ready in English, Reading, Math, and Science.

Cross-state comparisons of spending and achievement also demonstrate there’s no relationship between spending and achievement. An analysis prepared by Dr. Ben Scafidi prior to the release of the 2017 NAEP results shows that, between 1998 and 2015, Kansas had a 39 percent real (inflation-adjusted) per-student spending increase the reading score for low-income 4th graders only improved by two points, on a 500 point test. At the same time, the national average for spending grew much slower (24 percent) but Reading scores improved by 14 points. New York matched the 14-point national improvement but had a whopping 45 percent spending jump.

Florida, on the other hand, had a tiny spending gain of just 4 percent, but their Reading score shot up 30 points! Florida also has much stronger gains for other students and subjects, even while spending much less per-state each year; in 2015 for example, Florida spent just $10,168 per-pupil while Kansas spent $12,753.

The difference is that Florida has had a long-term focus on holding schools accountable. They have a robust public charter school system as well as other choice options for parents. Their pioneering 3rd-grade reading initiative – not promoting students to the 4th grade unless they could read at grade-level – has been adopted by many states, but not Kansas; legislators caved to pressure from unions and local school boards. Florida also introduced strong transparency measures, including an “A-F grading system” so parents know how their school is performing.

The difference is that Florida has had a long-term focus on holding schools accountable. They have a robust public charter school system as well as other choice options for parents. Their pioneering 3rd-grade reading initiative – not promoting students to the 4th grade unless they could read at grade-level – has been adopted by many states, but not Kansas; legislators caved to pressure from unions and local school boards. Florida also introduced strong transparency measures, including an “A-F grading system” so parents know how their school is performing.

By the way, Florida continues to spend much less per-pupil than Kansas; US Census data shows Florida spent $10,314 in 2017 while Kansas spent $13,196. Florida also outperformed Kansas on six of the eight NAEP measurements in 2017; Kansas did better on one measurement and they tied on the other.

Solving the school funding/student achievement puzzle

Now that the Court has signaled its intent to measure adequacy by only considering money, two things are relatively certain. The pall of school funding litigation will hang over taxpayers indefinitely, taking the focus away from actual education instruction. Also, schools not being held accountable for allocating resources to improve achievement will continue leaving thousands of kids behind, and with the Court using lack of educational improvement as ‘evidence’ of underfunding, school lawyers will use that as an excuse to sue for more funds to be spent in any manner they so choose.

It is therefore incumbent on the Legislature to advocate for students and advance K-12 policies that have the greatest chance of improving outcomes for students who are not getting the basic skills that will make them college or career ready.

Sound policies that will succeed have been proposed, and some even passed the House this year. Those policies should now pass and become law before more students are left behind.