School lawyers and some legislators are saying it will require $400 million to $800 million more per-year to satisfy the Court but that’s not what the Court said. State legislators should ignore those claims and focus on what the Supreme Court actually said: build a new school funding formula that is reasonable calculated so that students can meet the Rose standards. Funding levels in the past were not reasonably calculated, but merely set where votes could be obtained. And what really matters – actual student achievement – wasn’t even a distant thought in the old formula.

My colleague David Dorsey writes that there’s plenty of activism to criticize in the opinion to which legislators should firmly and constructively respond, including factual refutations in the preamble to the new formula. But healthy doses of activism aside, the Court left legislators in the driver’s seat. The question is whether the majority will take the wheel and put a new school funding formula in place to get students the education they deserve or succumb to institutional demands and prove Einstein’s definition of insanity.

Resurrecting the old formula isn’t an option

The Court reaffirmed its game-changing March 2014 decision on determining adequacy, saying it’s met “…when the public education financing system provided by the Legislature for grades K-12 – through structure and implementation – is reasonably calculated to have all Kansas public education students meet or exceed” the Rose standards of education capacities.

The old school funding formula made no attempt to calculate anything or address outcomes, so resurrecting it isn’t an option. Indeed, the Montoy and Gannon courts repeatedly criticized the Legislature for having no rational, calculated basis for its funding decision. As the Court says on page 9 of the opinion, “…the State will bear the burden of establishing such compliance and explaining its rationales for the choices made to achieve [adequacy].” Like it or it not, legislators have to create a new, reasonably calculated school funding formula.

By the way, the school funding formula that unions and most school officials support would cost at least $965 million more. It was introduced by Rep. Melissa Rooker, who admits that her plan does not attempt to address adequacy or outcomes; it’s just the old formula with more money.

Reasonably calculating adequate funding

The Court provides very clear guidance on the creation of a new school funding formula. On page 54, the lower court’s overreliance on “actual costs” is acknowledged but the Court goes on to say, “…nevertheless, actual costs remain a valid factor to be considered….” HB 2347 introduced by Rep. Ron Highland provides a template for calculating adequacy that takes actual costs into account and also considers outcomes achieved at those costs. (Adequacy could be calculated in other ways but HB 2347 is the only school funding formula proposed thus far attempts to reasonably calculated adequacy.)

HB 2347 uses this process to calculate adequate funding for Instruction for districts with enrollment below 400 students:

- Identify Instruction spending for each district, excluding spending from Funds for which funding is otherwise provided (KPERS, At Risk, SPED, etc.)

- Calculate the percentage of students (not low income) at Grade Level or better, averaging the percentages for Math and English Language Arts. Low income students are excluded because additional money (Poverty) is provided elsewhere.

- Calculate the average spend per-pupil of districts with at least 70% at Grade Level to arrive at what is adequate. (Note: 70 percent was the minimum but the actual average percentage of that group was 85 percent.)

The average spend per-pupil for those districts in the control group was $5,251 with 60 of those districts spending less than $5,251. The formula poses that it’s therefore reasonable to say that $5,251 per-student is adequate. Actual spending per-pupil for districts with enrollment below 400 students ranged from $4,096 to $8,996.

HB 2347 goes through the same calculations for other cost centers (Student Support, Staff Support, Administration, etc.) and then adds additional funding (Special Education, Poverty, English Language Learners, etc.).

The variables can be adjusted at legislative prerogative but the methodology in HB 2347 should be quite familiar to the Supreme Court, as it is essentially an honest version of Augenblick & Myers’ successful schools model. A&M was supposed to identify districts that met the 2001 definition of success and base their funding recommendation on the subset of those districts that were also efficient. Instead, A&M admittedly deviated from their own methodology and threw efficiency out the window; their cost study used by the Montoy courts therefore had inflated numbers.

Now you begin to see why union and school officials resist having funding reasonably calculated; it won’t produce the windfall they want.

The Legislature could demonstrate that adequacy can be reasonably calculated at the same or lower amount but politically speaking, it will likely require a little more spending to satisfy an activist Court. The key is presenting the Court with calculations that can be defended as reasonable and those calculations need not arrive at any particular level. Any amounts referenced in the Court’s opinion were based on the old A&M cost study and that is no longer the basis for adequacy. The Court may wish the number to be much higher but their own test is whether the calculations are reasonable, not the total funding provided.

Holding schools accountable for outcomes

Since the Court is holding the Legislature accountable for improving outcomes and closing achievement gaps, the Legislature must take steps to hold schools accountable. Otherwise, schools will continue to spend money as they see fit (with improving outcomes often not the deciding factor) and achievement will remain at unacceptable levels for low income students.

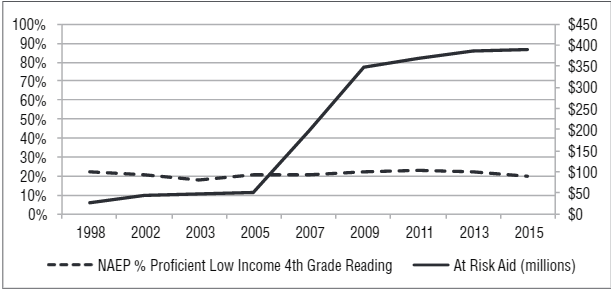

One important change in the new school funding formula would be to require that any money provided to close achievement gaps for low income students be spent for those students’ direct, exclusive benefit. Amazingly, that’s never been the case. The chart below shows the Legislature increased funding for At Risk students 7-fold between 2005 and 2015 but there was basically no change in Proficiency. The Legislature allowed that extra money to be spent on other things, and that’s what school boards did; both parties may have done so with the best intentions but the results speak volumes.

Holding school boards accountable for outcomes would perhaps be the most important element in the new school funding formula. School officials may say they are accountable in various ways but here’s the bottom line: to this day, if outcomes don’t improve or decline, there is no consequence. Well, except for the students who don’t get the education they deserve.

Holding school boards accountable for outcomes would perhaps be the most important element in the new school funding formula. School officials may say they are accountable in various ways but here’s the bottom line: to this day, if outcomes don’t improve or decline, there is no consequence. Well, except for the students who don’t get the education they deserve.

A reward-and-consequence approach ensures low income students aren’t trapped in under-performing schools, while encouraging school boards to make efficient, effective use of taxpayer money. First, implement a grading system for every school building based on state assessment scores with an emphasis on low income kids. Every building would be graded A through F, just like students, so parents and legislators clearly understand performance levels and progress.

Then, every building that maintains an A or improves a letter grade is rewarded with bonuses paid to building staff. But every student in an F school is eligible for an Education Savings Account to go to a public or private school of their choice. The consequence helps focus school boards’ attention on deploying resources in students’ best interest.

Conclusion

No amount of money has or will close achievement gaps, especially if simply dumped into an unaccountable system. Not in Kansas and not in the United States. The question facing each legislator is whether to base their decisions on institutional demands or what meets the Court’s test of adequacy. Every nod to institutions will come at the expense of students and taxpayers.