[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text](Editor’s note – this article has been updated with a revised calculation of virtual enrollment; the original article showed a 22,000 total enrollment decline. Some of the district enrollment changes are also updated.)

School districts’ decisions to add managers and cut classroom aides is the latest indication that legislators need to approve money-follow-the-child programs to get kids the education they deserve.

Preliminary enrollment shows a loss of more than 12,000 students statewide, but local school boards added 46 more managers while eliminating hundreds of classroom aides and special education paras.

Preliminary enrollment shows a loss of more than 12,000 students statewide, but local school boards added 46 more managers while eliminating hundreds of classroom aides and special education paras.

The KPI definition of management positions includes superintendents, assistant superintendents, principals, assistant principals, directors, instruction coordinators, and curriculum specialists.

Multiple districts choosing to not allow in-person learning this year probably account for so many classroom positions being eliminated but this also underscores school boards’ disregard for improving student achievement, as research clearly shows that virtual learning is no substitute for in-person instruction.

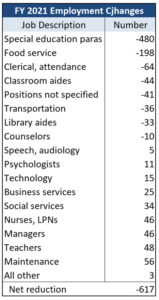

Total employment of 71,845 this year is lower than last year by 617 positions. Other job categories that were reduced include fewer food service workers (198), clerical and attendance service employees (64), regular education classroom aides (44), transportation workers (36), library positions (33), and counselors (10).

Some employment categories increased, however, including maintenance workers (56), teachers (48), nurses and LPNs (46), social services (34) and business services (25),

And while employment declined overall, some districts added jobs, including 109 districts that lost students.

And while employment declined overall, some districts added jobs, including 109 districts that lost students.

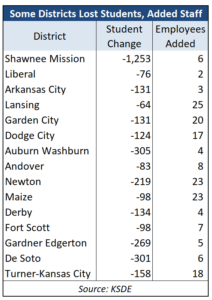

Three Johnson County districts lost students but added staff, including Shawnee Mission (lost 1,253 students, added six employees), Gardner-Edgerton (lost 269 students, added five employees), and De Soto (lost 301 students, added six employees).

Andover, in Butler County, lost 83 students but their personnel reports reflect eight more employees.

Garden City, in Finney County, lost 131 students but hired 20 more employees. Auburn-Washburn in Shawnee County and Maize in Sedgwick County also had significant enrollment declines (305 and 98, respectively) but added staff (4 and 23, respectively).

The state’s largest district, Wichita, lost 1,867 students and eliminated 82 positions.

Employment and enrollment comparisons for all school districts are available at KansasOpenGov.org. Enrollment numbers come from the 2021 Legal Max file prepared by the Kansas Department of Education and will be updated again following the February district census.

8% more students, 33% more staff since 1993

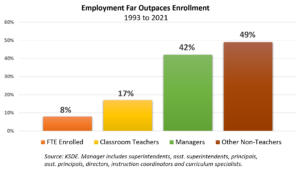

KSDE employment and enrollment records show an 8% increase in enrollment since 1993 but school district employment jumped 33%, from a little over 54,000 employees to almost 72,000.

Classroom teachers increased by 17%, there are 41% more special education teachers and reading specialists, management positions increased by 42%, and all other staff increased by 49%.

The student-teacher ratio dropped from 16.4 students per classroom teacher in 1993 to 15.1 this year. Class sizes, however, have reportedly increased although KSDE doesn’t publish that number. When class sizes are increasing but the student-teacher ratio is falling, that’s indicative of a management issue rather than a funding issue.

The student-teacher ratio dropped from 16.4 students per classroom teacher in 1993 to 15.1 this year. Class sizes, however, have reportedly increased although KSDE doesn’t publish that number. When class sizes are increasing but the student-teacher ratio is falling, that’s indicative of a management issue rather than a funding issue.

Legislative solutions

Hiring 18,000 more employees has had little impact on student achievement.

Reading proficiency on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) fell from 35% in 1998 to 33% in 2019 (average of 4th grade and 8th grade), and state assessment results show very low levels of college and career readiness.

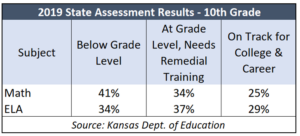

The 2019 state assessment results published by the Kansas Department of Education show 41% of 10th-graders are below grade level in Math; 34% are at grade level but still need remedial training, and only 25% are on track for college and career.

In English Language Arts, 34% are below grade level, 37% are at grade level but still need remedial training, and only 29% are on track for college and career. The state assessment wasn’t given in 2020.

In English Language Arts, 34% are below grade level, 37% are at grade level but still need remedial training, and only 29% are on track for college and career. The state assessment wasn’t given in 2020.

With money – particularly the potential loss of it – being the #1 motivator for school boards, legislators should create money-follow-the-child programs for students below grade level on the state assessment and kids with disabilities, including dyslexia. That provides immediate relief to students for whom their current school obviously isn’t working and should motivate school boards to focus resources on getting kids at least to grade level.

Another money-follow-the-child program is needed for students in schools that aren’t providing full-time in-person learning. Research shows that kids aren’t major COVID spreaders and cases in schools are relatively low, yet school boards are denying in-person learning to tens of thousands of students.

Legislators should also require school districts to certify that, in their opinion, they’ve allocated sufficient resources to the instruction section of their budgets so that all kids have an opportunity to reach grade level. School attorneys claim that having large numbers of kids below grade level somehow ‘proves’ that schools don’t have enough money, so at the very least, budget certification would weaken their arguments the next time they sue taxpayers.

School lobbyists, unions, and an alphabet soup of other organizations vehemently oppose money-follow-the-child programs and other efforts to hold school boards and administrators accountable. But until enough legislators muster the courage to fight them and override Governor Kelly’s inevitable veto, students will continue to suffer.

Rep. Kristey Williams, (R) – Augusta, who chairs the House K-12 Budget Committee, says districts should be allocating resources to maximize student achievement.

“Kansans should expect improved student achievement on all measurable categories. Otherwise, it would indicate a failure in our K-12 system to translate tax dollars and managerial policies to improved outcomes.”

She’s right, of course; parents should expect district officials to use resources in students’ best interest. But this year’s employment decisions are the latest in decades of district actions that prioritize institutional interests over students.

And that won’t change until legislators intervene, starting with robust money-follow-the-child programs.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]