With the State of Kansas facing up to a $1 billion shortfall next year in an $8 billion General Fund budget, there can be no ‘sacred cows’ exempt from COVID budget cuts. K-12 education consumes about half of the budget and with $843 million in funding, higher education takes another 11%.

Most legislators knew the state couldn’t afford to pay the ransom demanded by the Kansas Supreme Court and school districts without imposing more tax hikes that would exacerbate an already weak economy. House Speaker Ron Ryckman addressed the House on April 19, 2019, explaining that he couldn’t support SB 16 because it was a promise that likely couldn’t be kept.

“Six things would have to happen in order for the Legislature and the Governor to keep this promise. First, the Supreme Court would have to rule in favor of funding that isn’t based in their opinion. We’ll have to raise taxes. We will not be able to lower the food sales tax. We’d have to keep the Bank of KDOT open. We will not be able to make KPERS payments, and there cannot be a recession. That’s not the kind of promise I can make.”

When SB 16 was being debated in conference committee, sources tell us attempts were made to limit the increase and remove the inflation escalator clause. Some legislators were in favor but others would only agree if the governor would go along.

Governor Laura Kelly declined, however. One highly placed source asked her what she would do if the state ran short of money, and she replied, “Well if we can’t afford it, I’ll just tell the court we can’t afford it.”

Well, the recession is here. It was only a matter of when, not if, and most economists expect this one to be worse than the Great Recession about ten years ago. So now (finally) it’s time for Governor Kelly and the Legislature to do what should have been done years ago – tell the courts ‘thanks for your opinion, but we’ll take it from here and do what we think is appropriate.’

Even Senate Minority Leader Anthony Hensley, a Topeka Democrat and one of the governor’s closest allies said, “I don’t know if she has any choice but to cut funding for K-12 education,” said.

Courts have no authority to set funding levels

The Kansas Supreme Court’s 1994 ruling in USD 229 v. State of Kansas declared that “suitable provision for finance” in the Kansas constitution does not refer to a level of funding, but to a system of finance which, as stipulated in the constitution, may not include tuition. “Adequate” isn’t part of the constitutional language on education; that adjective was created by courts.

The Kansas constitution also clearly says that only the Legislature may appropriate funds. After a lot of criticism of the Montoy court for ordering a specific amount in 2005, the Gannon court tried to pretend it wasn’t doing so and used the ‘Goldilocks’ approach – ‘no, it’s still not quite right…try again.’ But that’s akin to Vito Corleone ‘asking’ someone to do something.

Giving further credence to unconstitutional actions by the Kansas courts will either devastate funding for all other state services or force more tax increases on taxpayers who are already clinging for economic life.

Spending more than necessary

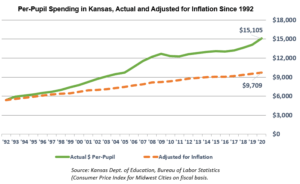

Kansas public schools spent $2.6 billion more last year than if per-pupil spending had increased for inflation since 1992. Spending would have increased from $5,416 per pupil to $9,709 per pupil adjusted for inflation but the Department of Education estimates spending will be $15,105 this year.

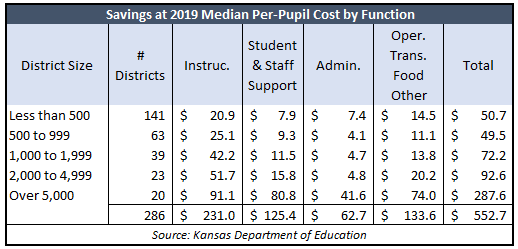

The spending patterns of the state’s 286 districts also shows opportunities to save money. Districts with similar enrollment often spend a lot more (or less) than others on the same function. For example, the per-pupil amount spent on Administration in districts with enrollment between 2,000 and 5,000 students ranges from as little as $844 per pupil in Shawnee Heights to as much as $1,729 in Turner-Kansas City. In districts with enrollment over 5,000 students, De Soto spends the least, at $734 per pupil, and Topeka spends the most at $1,768.

We did the analysis of each operating cost center – Instruction, Student Support, Staff Support, Administration, Operations & Maintenance, Transportation, Food Service, and Other. Taxpayers and districts would save $553 million if the districts spending more than the median cost were at the median. There may be valid reasons why that couldn’t be done in some cases, but it’s also possible that districts could spend less than the current median if they wanted.

We did the analysis of each operating cost center – Instruction, Student Support, Staff Support, Administration, Operations & Maintenance, Transportation, Food Service, and Other. Taxpayers and districts would save $553 million if the districts spending more than the median cost were at the median. There may be valid reasons why that couldn’t be done in some cases, but it’s also possible that districts could spend less than the current median if they wanted.

Not spending all the funding they receive

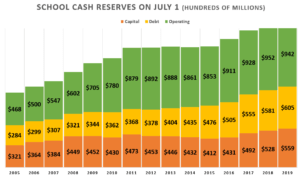

In addition to spending more than necessary, school districts haven’t spent all the state and local tax dollars they receive. District operating cash reserves, shown in green on the chart below, increased from $468 million in 2005 to $942 million last year. Most of the $474 million increase in those reserves represents state and local tax dollars that weren’t spent. (Government funds operate just like your checkbook; the balance increases when deposits – tax dollars – exceed spending.)

The biggest gains came following the 2005 court-ordered spending increase, which further disputes school officials’ claims that they didn’t – and still don’t – have enough money. Every excuse offered by school officials for the increase in these reserves has been refuted, and most often, using their own actions. For example, the 2005 average ratio of operating cash on hand at the beginning of the year as a percentage of that year’s operating expense was 12.3%. Not a single district said that wasn’t enough back then…of when it was 16% a few years later. The carryover ratio was 18.4% last year, but now districts say it’s not enough.

What changed? Kansas Policy Institute uncovered the existence of the money in 2010 and informed legislators. Until then, legislators and even school board members didn’t know districts had all that money in reserve.

Requiring districts with excess funds to use them will be on the list of education savings opportunities coming soon.

No relationship between spending and achievement

Parents and legislators needn’t worry that achievement will suffer if schools operate more efficiently, as an honest review of the facts shows no relationship between spending and achievement.

The chart below shows the Department of Education estimates spending will be $15,105 per pupil this year, or almost $4,500 per student above long term inflation. Despite such large spending hikes, reading proficiency is lower than in 1998, with only a third of students being proficient.

My colleague David Dorsey compared cost-of-living-adjusted spending per pupil for all 50 states against achievement levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). According to U.S. Census data for 2017, Kansas had the 27th highest spending at $13,196 per pupil. But the dollar goes a lot farther in Kansas than most states, so adjusting all states for cost of living variances, Kansas is ranked #17, with $14,911 while the national average was $14,275.

Kansas is usually in the middle of the pack on NAEP scores and ranked #27 in 2019. And measuring productivity as dollars spent for each point of achievement on NAEP show Kansas has low productivity relative to most states, ranked #34. Seventeen states spent less per pupil than Kansas but had higher NAEP scores.

Conclusion

Legislators should now tell the courts what they should have years ago – ‘thanks for your opinion, but we’ll take it from here.’

Media and education officials will threaten to have legislators tossed out of office, but leaders are able to face the music and make the tough but necessary decisions. And Kansas needs leaders now more than ever.

Education officials will claim they couldn’t possibly spend less, but my next column will outline some of the many ways it can be done.