There isn’t a single legitimate study proving that spending more money caused achievement to improve (proving causation is much different than believing in the notion), but that’s the underlying premise of KASB’s spending and achievement claims. Money matters, but it’s how money is spent that can make a difference, and achievement will remain stubbornly low for many students until (1) enough parents understand the true nature of achievement in Kansas, and then (2) pressure legislators to hold school boards accountable.

The refutation of their spending claims below compliments our rebuttal of another KASB falsehood, asserting that Kansas has the ninth-highest academic achievement in the nation. KASB’s claim, unfortunately, isn’t true; national performance rankings on the ACT and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) range from the mid-teens to the low 30s. Overall, Kansas is about average in a nation that doesn’t do very well.

KASB deceptive claims on inflation

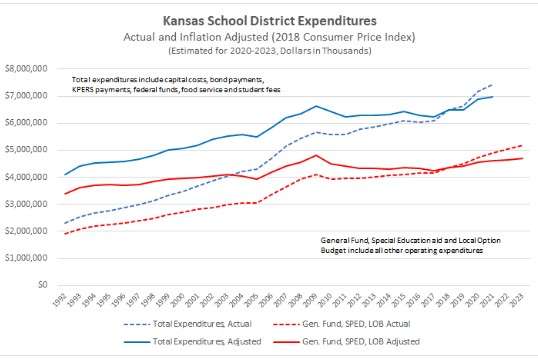

KASB contends that most of the $1 billion school funding increase added over the last three legislative sessions “…will only replace purchasing power lost to inflation since 2009.” Their conclusion is distorted by restating prior years’ funding in constant 2018 dollars. The screengrab below shows 1992 spending of a little over $2 billion was restated to more than $4 billion, giving the appearance that funding was below inflation-adjusted levels until 2018.

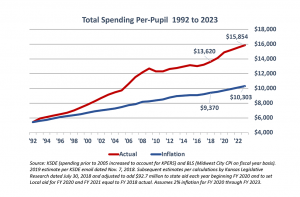

In reality, spending has grown much faster than inflation since 1992. The per-pupil inflation comparison shown next also accounts for the increase in enrollment, and it adds KPERS funding to reported totals from 1992 through 2004 (KPERS is included in the reported numbers since 2005).

In reality, spending has grown much faster than inflation since 1992. The per-pupil inflation comparison shown next also accounts for the increase in enrollment, and it adds KPERS funding to reported totals from 1992 through 2004 (KPERS is included in the reported numbers since 2005).

The blue line shows per-pupil actual funding of $5,416 in 1992 would have grown to $9,370 in 2018 if just increased for inflation; actual funding of $13,620 was, therefore, $4,250 per-pupil above inflation last year.

Estimates provided by the Department of Education and Kansas Legislative Research shows funding will grow to $15,854 per-pupil in 2023 and be $5,551 above long-term inflation. Actual funding will likely be higher because the KSDE / KLRD estimates assume no increase in federal funding and very little change in local funding.

Below the national average

KASB says per-pupil funding has fallen behind the national average since 2009, but Kansas has always been behind the national average, and more important, comparing spending to the national average is a meaningless measure of whether schools are educating students. And with Kansas’ cost of living being lower than the national average, spending should be below average.

But rest assured, Kansas is above the national average on some measures KASB didn’t mention:

- #6 in debt per-student

- #9 in capital spending per-student

- #11 in cash per-student

- #15 in state aid per-student

School board entitlement mentality

KASB says school spending will be a lower share of total personal income than in prior decades, which merely reflects an entitlement mentality; local school boards believe they are entitled to a share of Kansans’ income. That aside, personal income as calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis includes things that aren’t available for paying taxes, like employer contributions to retirement, health insurance and social security, and government transfer payments. By pushing this entitlement narrative, your local school board is effectively asking you to pony up more taxes for them if the cost of your health insurance goes up and your employer picks up part of the cost. Government transfer payments include things like Medicaid, the Children’s’ Health Insurance Program (CHIP), welfare payments, and unemployment benefits; as these costs increase, your local school board thinks you should have to pay higher taxes so they get a pay increase!

But an honest comparison of personal income elements available to pay taxes shows school spending increased 182 percent since 1992, while personal income available to pay taxes grew by 180 percent.  If local school boards and administrators really believe school funding should be a percentage of personal income, they would have asked for a funding cut between 2001 and 2011 when school spending was growing much faster than income to pay taxes. Instead, they sued you for more money.

If local school boards and administrators really believe school funding should be a percentage of personal income, they would have asked for a funding cut between 2001 and 2011 when school spending was growing much faster than income to pay taxes. Instead, they sued you for more money.