The Kansas Department of Education confirmed this week that per-pupil funding is estimated to be $16,216 this year; that’s 9.2% higher than last year’s record level of $14,848. KSDE Deputy Commissioner of Finance Craig Neuenswander confirmed the numbers in an email to KPI.

Per-pupil funding from the State is estimated to be $10,967; federal aid is $1,312 and the local portion is estimated at $3,937.

Per-pupil funding from the State is estimated to be $10,967; federal aid is $1,312 and the local portion is estimated at $3,937.

Total funding is expected to increase by about $239 million, including a $99 million increase in state aid, $105 million in federal aid, and about $34 million in local aid.

But that aid will be spread over about 25,000 fewer students. Some parents have pulled their kids out of public schools that are not offering full-time in-person learning.

KSDE estimates enrollment will drop to 451,000 this year, which is less than it was in 2010.

Districts still paid for students who left

A 5% enrollment decline would have caused funding to go down, but school districts lobbied the legislature for changes in the funding formula so that money is allocated based on prior enrollment. They told legislators it was easier for them to budget over the summer if they knew the number of students for which they would be funded. So now that some districts aren’t offering full-time in-person learning, they get paid for students who left and school boards don’t have a financial incentive to safely open schools (as is being done in many cases in Kansas and across the nation).

It’s difficult to put an accurate number on how much extra money taxpayers are giving to school districts without knowing which students left, as some students qualify for more money than others. Special education students and those considered ‘at risk’ generate additional funding (among other weightings) and some costs, like KPERS pension funding, are based on payroll rather than enrollment.

That said, it’s a really big number. For example, if the per-pupil funding averages just $10,000 each, taxpayers will be spending $250 million more this year than necessary. And with the state facing over a $1 billion deficit and thousands of people out of work, that’s one heck of a lot of unnecessary spending.

Just spending more doesn’t improve achievement

With history as our guide, all that extra money won’t make a dent in the state’s persistently low achievement results.

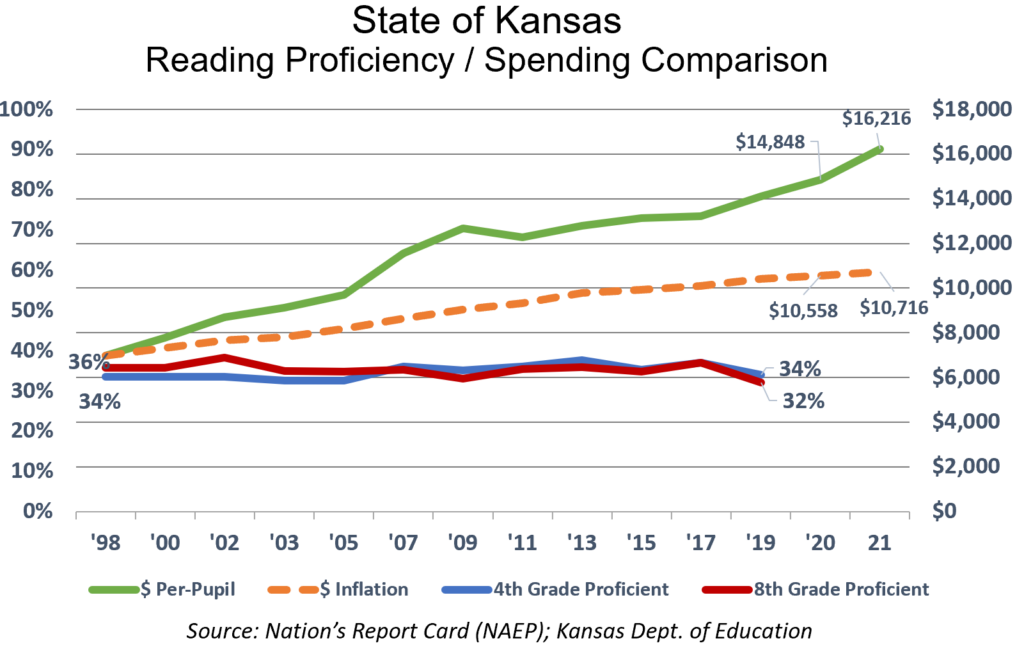

Per-pupil funding would have grown from $6,985 in 1998 to $10,558 last year if it was increased for inflation, but actual funding was $14,848. That means taxpayers spent a little over $2 billion more last year (at a $4,290 per student premium over inflation).

But even though funding has far outpaced inflation, Reading proficiency is lower than in 1998. Eighth-grade proficiency Reading proficiency was 36% on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) but fell to 34% in 2019; fourth-grade proficiency fell from 34% to 32%.

College-readiness levels on the ACT show the impact on older students. In 2002, just 24% of the Kansas students who took the test were considered college-ready in English, Reading, Math, and Science; results were a little better in 2019 at 27%, but certainly not what most people would consider acceptable.

College-readiness levels on the ACT show the impact on older students. In 2002, just 24% of the Kansas students who took the test were considered college-ready in English, Reading, Math, and Science; results were a little better in 2019 at 27%, but certainly not what most people would consider acceptable.

For kids’ sake, here’s hoping that parents’ fury over their children not being allowed in school full-time will carry over to the 2021 legislative session and help convince enough legislators that real accountability measures are needed.