The February 11 Supreme Court decision ruling declaring that two pieces of state aid are not equitably distributed creates some opportunities and challenges for the Legislature. One big opportunity is the development of a new method to equitably distribute capital outlay and supplemental general state aid (Local Option Budget equity) without necessarily spending a lot more money for the current year. The Court reaffirmed that constitutional infirmities “can be cured in a variety of ways—at the choice of the legislature” with the proviso that any adjusted funding must also meet a separate test of adequacy – i.e., whether districts are receiving ‘enough.’

The Legislature modified the equity formula to provide proportional funding to eligible districts but the Court said that amounts to under-funding the equity formula. The Court also ruled that equity funding cannot be ‘frozen’ as has been done under the block grant but must be adjusted annually according to the formula.

Equity system favors big districts

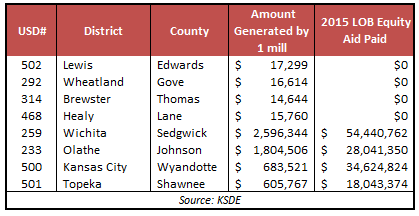

Equity is a constitutional construct that must be met, but putting more money into the  existing equity system would be a perversion of the concept, as much of the increase would go to districts with high property values. Equity is distributed based on per-pupil valuation, so tiny districts where 1 mill of property tax generates less than $25,000 are considered ‘wealthy’ and ineligible for extra aid but districts in wealthy Johnson County are all considered ‘poor’ and in need of extra aid

existing equity system would be a perversion of the concept, as much of the increase would go to districts with high property values. Equity is distributed based on per-pupil valuation, so tiny districts where 1 mill of property tax generates less than $25,000 are considered ‘wealthy’ and ineligible for extra aid but districts in wealthy Johnson County are all considered ‘poor’ and in need of extra aid

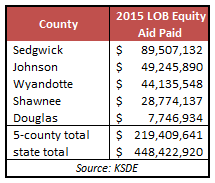

Citizens and media might think equalization money goes to small counties with low property values, but the per-pupil valuation method favors the big counties. In fact, 49 percent of Local Option Budget equalization money went to the five counties with highest total  assessed valuation last year. Distributing equity funding based on total valuation rather than per-pupil valuation would be a good option to consider. Another option was explored in the 2015 Legislative session; SB 71 would have equalized against the per-pupil valuation of Shawnee Mission (Johnson County), which has the highest total valuation. Districts with per-pupil valuation below Shawnee Mission would be eligible for equity aid based on their relative variance to the Shawnee Mission valuation per-pupil.

assessed valuation last year. Distributing equity funding based on total valuation rather than per-pupil valuation would be a good option to consider. Another option was explored in the 2015 Legislative session; SB 71 would have equalized against the per-pupil valuation of Shawnee Mission (Johnson County), which has the highest total valuation. Districts with per-pupil valuation below Shawnee Mission would be eligible for equity aid based on their relative variance to the Shawnee Mission valuation per-pupil.

The current cut line for equity eligibility is the 81.2 percentile of per-pupil valuation, which was arbitrarily established years ago. Legislators had a specific amount of money to spend and simply drew the eligibility line where that specific amount would be spent. The SB 71 method draws the line on a rational basis and also brings total valu

ation into play.

This spreadsheet shows Local Option Budget equity allocations by district under several scenarios: actual equity paid in 2013-14, block grant equity in 2014-15, full equalization under the current formula and 2014-15 calculation from SB 71.

Political challenges

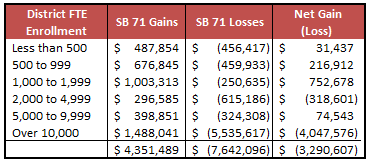

Developing a new equity distribution formula presents a number of political challenges. SB 71 would provide more money to 115 districts but 177 districts would receive less.  Smaller districts that are arguably more in need of equalization would see net gains while net losses would be concentrated in large districts. Unlike the current arbitrary 81.2 percentile methodology, an SB 71-like formula would be rationally derived. But how many legislators would vote for such system if their district loses even a tiny amount of funding in the base year? Would Johnson County legislators object to Blue Valley and Shawnee Mission being declared ‘wealthy’ instead of ‘poor’?

Smaller districts that are arguably more in need of equalization would see net gains while net losses would be concentrated in large districts. Unlike the current arbitrary 81.2 percentile methodology, an SB 71-like formula would be rationally derived. But how many legislators would vote for such system if their district loses even a tiny amount of funding in the base year? Would Johnson County legislators object to Blue Valley and Shawnee Mission being declared ‘wealthy’ instead of ‘poor’?

The large urban districts have a decided political advantage over small rural districts. Some use taxpayer money to employ full time lobbyists and since the big districts pay higher dues (more taxpayer money) to the Kansas Association of School Boards, the big guys tend to have more sway there as well. Union political power also favors the big districts because, as bank robber Willie Sutton said, that’s where their money is found.

Some legislators would likely object to anything that doesn’t spend millions more, but if history is any guide, most wouldn’t say which tax they would increase or which budget they propose to cut to balance the budget.

Creating a new equity allocation method is a good opportunity, but angst over the court’s threat to close schools may produce an even greater opportunity – convincing enough legislators to move forward with an entire new student-focused school funding system that holds districts accountable for outcomes and efficient use of taxpayer money. Doing so would finally putting the old system, block grants and related court battles in the rear view mirror.

And then perhaps the focus can shift to the real education crisis. For all the hue and cry over money, Kansas doesn’t have a money crisis; funding continues to set records, districts continue to operate very inefficiently and some aren’t even spending all of the money they receive. The real crisis is in student achievement, but districts don’t want to talk about it.