The Kansas Department of Education says school funding will increase by more than $500 million this year, but a review of district budgets indicates no shift in spending patterns and that’s not good news for students. It’s also not surprising, given that there is zero accountability for local school boards and administrators to improve achievement.

Following the previous court-ordered spending increase, the Legislature encouraged districts to put the new money into Instruction. The KSDE Accounting Manual says Instruction accounts for direct interactions between teachers and students; this ‘bible’ of school spending says, “Although all other functions are important, this function acts as the most important part of the education program, the very foundation on which everything else is built. If this function fails to perform at the needed level, the whole educational program is doomed to failure regardless of how well the other functions perform.”

Local school boards and administrators ignored the legislature’s policy recommendation as well as the KSDE Accounting Manual guidance and continued to allocate barely half of total spending to Instruction. This time around seems like déjà vu all over again.

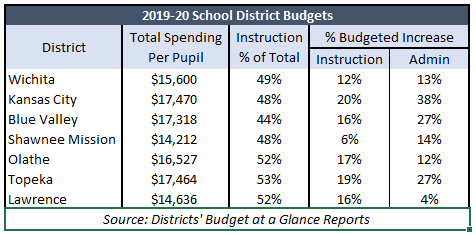

Some school districts still haven’t posted all their budget reports on their websites as required by state law, but the adjacent table shows a  recap from the state’s seven largest districts. Four of the seven (Wichita, Kansas City, Blue Valley, and Shawnee Mission) are budgeting less than half of total spending for Instruction and the other three (Olathe, Topeka, and Lawrence) are barely above 50%.

recap from the state’s seven largest districts. Four of the seven (Wichita, Kansas City, Blue Valley, and Shawnee Mission) are budgeting less than half of total spending for Instruction and the other three (Olathe, Topeka, and Lawrence) are barely above 50%.

Five districts (Wichita, Kansas City, Blue Valley, Shawnee Mission, and Topeka) are budgeting larger spending increases on Administration than on Instruction. Kansas City is the worst offender, budgeting a 38% jump in Administration spending; Blue Valley and Topeka are each budgeting a 27% increase for Administration.

Spending by cost function for last year isn’t published yet but personnel reports show that only 45% of the more than 2,000 staff additions were Instruction positions (teachers, teacher aides, and special education paraeducators). USD 500 Kansas City, one of the plaintiffs that sued taxpayers, reduced Instruction staff but hired 253 more employees in other areas.

Achievement: the real education crisis

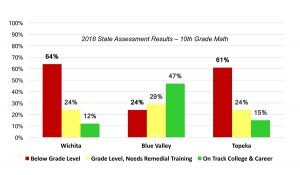

School districts and media are hyper-focused on money, but low student achievement is the real education crisis in Kansas. On average, only 24% of 10th-grade students are on track to be college and career ready in math, according to the latest state assessment results. Even worse, 44% are below grade level; the remaining 32% are at grade level but still in need of remedial training to be on track for college and career.

Achievement is disconcerting even in the more affluent suburbs. USD 229 Blue Valley in Johnson County is often considered the ‘best’ district in Kansas but even there, a quarter of 10th-grade students are below grade level and less than half are on track for college and career. The majority of 10th-graders in Wichita and Topeka – 64% and 61%, respectively – are below grade level and no more than 15% are on track for college and career. In addition to an absolute disservice to students and parents, student achievement in Kansas is a drag on economic growth across the state. And that won’t change with local school boards’ business-as-usual spending approach.

The majority of 10th-graders in Wichita and Topeka – 64% and 61%, respectively – are below grade level and no more than 15% are on track for college and career. In addition to an absolute disservice to students and parents, student achievement in Kansas is a drag on economic growth across the state. And that won’t change with local school boards’ business-as-usual spending approach.

School districts resist accountability

School districts expect legislators to be held accountable for giving them more money, but they resist all real accountability measures directed at them.

Our media subsidiary, The Sentinel, reported last March that the House of Representatives barely passed a proposal on a 63-60 vote but the Senate didn’t get a chance to vote on it. If passed, districts would have been required to create and publish accountability reports for student achievement and to certify that sufficient money has been allocated to Instruction spending so that students can meet the required outcomes.

Educators fought hard against the bill but until school boards and administrators are held accountable, two things are certain. First, nearly a third of students will remain below grade level (according to state assessment tests). Second, districts will eventually be suing again because the court says having large numbers of kids below grade-level somehow proves schools don’t have enough money.