New data from the Kansas Department of Revenue shows county property tax assessed by Kansas’ 105 counties increased by 154 percent over the last 20 years. That’s 2.6 times faster than the combined change in inflation (47 percent) and population (12 percent). To put than in perspective, had property taxes just kept pace with inflation and population, county property tax would have been $520 million less in Kansas last year, or about 37 percent lower.

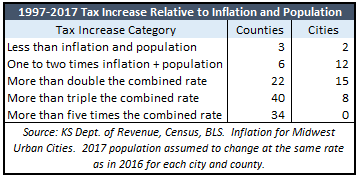

Grant County actually reduced its property tax and two counties – Hamilton and Stevens – increased property tax by less than the  combined rate of inflation and population for their counties. Six counties increased taxes in excess of inflation and population but by less than two times the combined total and 22 counties hikes taxes between two and three times the combined rate. The majority of counties hit taxpayers even harder; 40 counties increased property tax by three to five times inflation plus population and 34 counties hiked taxes at a multiple of five or greater.

combined rate of inflation and population for their counties. Six counties increased taxes in excess of inflation and population but by less than two times the combined total and 22 counties hikes taxes between two and three times the combined rate. The majority of counties hit taxpayers even harder; 40 counties increased property tax by three to five times inflation plus population and 34 counties hiked taxes at a multiple of five or greater.

Most of the 37 largest cities in Kansas also had tax increases much greater than inflation and population but as shown in the adjacent chart, not quite as onerous as counties.

Graphs depicting the 20-year change in taxes, mill rates, inflation and population for each county can be found here. The same information for cities can be found here.

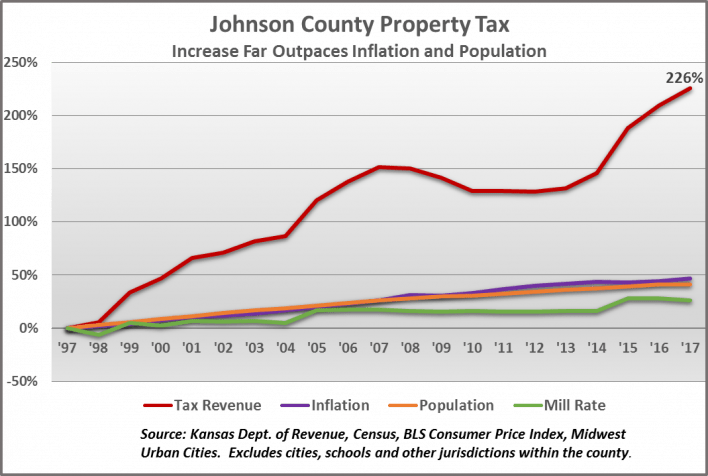

Johnson County increased property taxes by 226 percent over the last twenty years, right at the state average of 2.6 times the combined rates of inflation and population. Sedgwick County commissioners have traditionally taken a more fiscally conservative approach; their 95 percent tax increase is 1.5 times inflation and population.

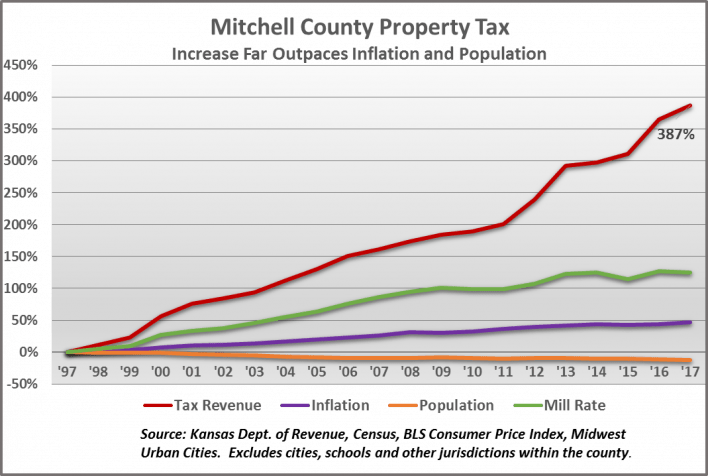

Jewell County in north central Kansas has the worst ratio, with a tax increase of 11.2 times the combined rate of inflation (47 percent) and a population decline of 29 percent. Mitchell County was almost as bad, with a tax increase of 11.1 times inflation and population.

Jewell County in north central Kansas has the worst ratio, with a tax increase of 11.2 times the combined rate of inflation (47 percent) and a population decline of 29 percent. Mitchell County was almost as bad, with a tax increase of 11.1 times inflation and population.