“Of course, I want people to have healthcare; I just didn’t realize I would be the one who was going to pay for it personally.”

That’s what Cindy Vinson—a retired California teacher and proud supporter of President Barack Obama—told the San Jose Mercury News when she learned of the insurance plan substitution and corresponding premium hike she would face under the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare). Kansas legislators ought to commit Vinson’s realization to memory. This year’s legislative session has ended without having to address murmurs calling for Medicaid expansion in the Sunflower State. However, this does not mean that the issue is a dead one in Kansas. With the 2014 elections on the horizon and Governor Brownback on the ballot, proponents of Medicaid expansion could very well attempt to revive the issue by thrusting it into the election season policy spotlight. Thus, an understanding of the true fiscal implications of Medicaid expansion in Kansas remains of the utmost importance to Kansans.

At its core, expanding Medicaid eligibility to those living at 138% of the federal poverty level is Obamacare’s answer to the rising tide of healthcare costs that often go uncompensated when uninsured individuals visit emergency rooms for treatment. In turn, when medical facilities cannot count on compensation for these costs, they must resort to driving up the costs of both emergency and non-emergency care for all individuals (both insured and uninsured) to cover potential shortfalls. Place Medicaid expansion alongside Obamacare’s “individual mandate,” and it becomes obvious that the law “bets” heavily on closing the uncompensated care gap to bring down overall healthcare costs.

Enter the June 2012 Supreme Court ruling on Obamacare, which gave states autonomy over whether or not to expand their existing Medicaid programs as envisioned above, and the Medicaid expansion question Kansas faces begins to crystallize. Nationally, the split between states choosing expansion and forgoing expansion to this point remains even (with Kansas still in the non-expansion camp). Proponents of expansion in Kansas have been enticed by the federal government’s offer to fund the full costs of expansion until 2016 and 90% of the costs thereafter. They are touting it as a “win-win,” “no-brainer” scenario tantamount to “free money.” Yet, anyone familiar with the old adage about a purported “free lunch” can probably guess that there is no such thing as free money or free healthcare either for that matter.

Even if a healthcare provider serves a patient “free of charge,” the services rendered are never truly “free.” Instead, the associated costs (time, supplies, etc.) are simply assumed or absorbed by an entity other than the patient. The concept of “free money” is a similar illusion. As the old sayings go, money never truly appears spontaneously by “growing on trees” or “falling out of the sky.” Some person or entity must earn it through work, production, and value creation. This fact makes the idea of “free federal money” doubly illusory because the federal government cannot create value or wealth on its own. Rather, it can only confiscate wealth already earned by U.S. taxpayers to pay its bills. Thus, even the federally funded portion of a potential Medicaid expansion in Kansas cannot be thought of as cost-free to Kansans. It is simply a redistribution of tax money Kansans and others across the country have already sent to Washington.

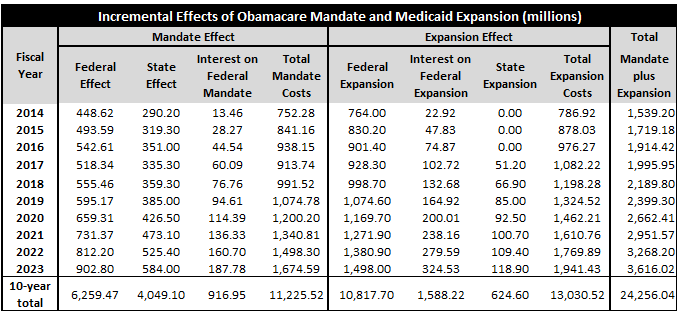

Setting aside this logical fallacy that is “free federal money” for the moment, let’s look at the work of current Social Security Advisory Board Member Dr. Jagadeesh Gokhale—who is also KPI’s own Adjunct Health Policy Fellow and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C. Dr. Gokhale has explored the fiscal implications of Medicaid expansion in Kansas specifically. His results (in the table below) show that the enrollment dynamic Obamacare’s “individual mandate” creates is already costing Kansas more than $4 billion in added healthcare expenses over the next ten years. That equates to almost $1,400 per Kansan in new healthcare costs over the period. Add in the Medicaid expansion element if Kansas chooses that path, and our state will add another $624.5 million to its Obamacare debt tab. This brings the tally of new healthcare costs per Kansan to more than $1,600 over the aforementioned ten-year period.

And that’s assuming the federal government makes good on its offer to use federal revenue to foot the rest of the bill as promised! For just Kansas’ expansion alone, the “rest of the bill,” will amount to more than $12.4 billion (or nearly $4,287 in new healthcare costs per Kansan). Admittedly, some Kansans may be inclined to dismiss this possibility of the federal government reneging on its funding promise as purely hypothetical. However, recent history proves that this possibility is in fact closer to reality than to conjecture at this point.

And that’s assuming the federal government makes good on its offer to use federal revenue to foot the rest of the bill as promised! For just Kansas’ expansion alone, the “rest of the bill,” will amount to more than $12.4 billion (or nearly $4,287 in new healthcare costs per Kansan). Admittedly, some Kansans may be inclined to dismiss this possibility of the federal government reneging on its funding promise as purely hypothetical. However, recent history proves that this possibility is in fact closer to reality than to conjecture at this point.

During the U.S. Congress’ now infamous “Supercommittee” deficit reduction talks of 2011, President Obama proposed simplifying and streamlining the funding formulas that determine how much federal money states receive to administer their Medicaid programs. He touted his “blended rate” idea as a cost-saving measure poised to reduce federal Medicaid spending by $100 billion over the next decade. Yet, even the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C. decried the measure as one that would shift significant costs to states; exacerbate barriers to specialist care that Medicaid recipients already face; and create few—if any—of the administrative cost-efficiency savings it advertised.

Aside from these obvious flaws though, perhaps the most fundamental lesson of relevance to this blog post is that the federal government already has a penchant for cutting Medicaid funding to states. What’s more, it hasn’t exactly displayed an identical penchant concerning Medicare cuts to healthcare providers serving seniors, but its involvement in that process features a similar ominous sense of uncertainty.

In 1997, the Congress passed the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate Program (SGRP) as a federal cost control mechanism designed to cut Medicare reimbursements to participating doctors if per-patient treatment costs exceeded federal spending targets for any given year. Yet, as the AARP points out in a recent blog post on the issue, Congress has ultimately delayed these cuts seventeen times in the last eleven years in a process known cheekily around D.C. as the “doc fix.” This year, Congress waited until March 31, 2014 (just one day before a 24% cut in reimbursement rates was set to take effect) to pass its annual fix. The AARP laments the legislative reticence and procrastination constantly surfacing around this issue and considers these elements to be chief drivers of uncertainty for seniors about whether their trusted treatment professionals will be able to continue seeing them. Indeed, the organization cannot help but to point out the striking resemblance the dynamic bears to the repetitive time warp on display in Bill Murray’s 1993 comedy Groundhog Day. Each year, Congress promises to revisit the “doc fix” issue in a deeper, more permanent, and bipartisan way to no avail.

Taken together, the above anecdotes from both Medicaid and Medicare are not just obligatory history lessons to be tossed aside later into the proverbial “ash heap” or “dustbin” where such lessons often go. Rather, they should cause Kansans to wonder why our same federal government that seems to crave financial uncertainty when it comes to healthcare costs should be trusted to act any differently when it comes to Medicaid expansion in Kansas under Obamacare.

Kansans beware: This offer of a Medicaid expansion-themed “free lunch” invitation from an already cash-strapped Uncle Sam will more likely turn into a federal “dine and dash.”

[1] “Cost Per Kansan” figures calculated using 2013 U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates for Kansas