Contrary to hyperventilating political claims, Kansas’ private sector employment is slightly more competitive post-tax reform in comparison to other states with a personal income tax. And aside from a few issues unrelated to state tax policy, private sector employment gains outpaced three of Kansas’ four neighboring states.

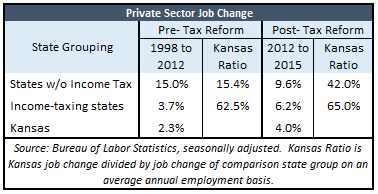

Over the fourteen years preceding tax reform, Kansas private sector jobs grew 2.3 percent  (in total, not annually), or just 62.5 percent of the average growth for states than tax income and only 15.4 percent of the average growth enjoyed in the nine states without an income tax. Over the last three years, private sector employment increased by 4.0 percent and improved to 65 percent of its income-taxing peers and 42 percent of the growth rate for states that don’t tax personal income.

(in total, not annually), or just 62.5 percent of the average growth for states than tax income and only 15.4 percent of the average growth enjoyed in the nine states without an income tax. Over the last three years, private sector employment increased by 4.0 percent and improved to 65 percent of its income-taxing peers and 42 percent of the growth rate for states that don’t tax personal income.

These gains may not be the ‘shot of adrenaline’ predicted by Governor Brownback and while it’s fair to criticize any political prognostication, some perspective is also in order. His statement accompanied passage of a massive tax reform package that was never fully implemented. The plan passed in 2012 could have been implemented with a one-time 8 percent efficiency improvement in state spending but Governor Brownback, Democrats and many Republicans resisted cost reductions, which resulted in a tax increase and higher spending in 2013. The same happened again in 2015. There is still a net reduction in the tax burden, but nowhere near what was passed in 2012.

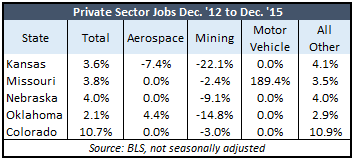

Honest measurement of whether something is ‘working’ requires the elimination of unrelated factors, such as government employment. Tax reform was not intended to grow government bureaucracy so we look at private sector employment rather than Non-Farm (which includes government). The private sector composition also varies considerably from state to state, so it’s also important to examine changes in certain sectors for relevance.

Kansas, for example, is much more dependent upon aerospace and Mining (which includes oil and gas, forestry and other mineral extractions) than most states, and those sectors have been hit hard recently for reasons unrelated to state tax policy. Missouri meanwhile benefited from thousands of auto manufacturing jobs being restored, but Kansas doesn’t have enough jobs in that sector to meet minimum reporting requirements. Looking at the remainder of the private sector workforce for neighboring states (at least 96 percent of total), Kansas outperformed Missouri, Nebraska and Oklahoma over the last three years and trailed Colorado (which has been the case for a very long time thanks in part to their controlled spending and lower taxes).

have been hit hard recently for reasons unrelated to state tax policy. Missouri meanwhile benefited from thousands of auto manufacturing jobs being restored, but Kansas doesn’t have enough jobs in that sector to meet minimum reporting requirements. Looking at the remainder of the private sector workforce for neighboring states (at least 96 percent of total), Kansas outperformed Missouri, Nebraska and Oklahoma over the last three years and trailed Colorado (which has been the case for a very long time thanks in part to their controlled spending and lower taxes).

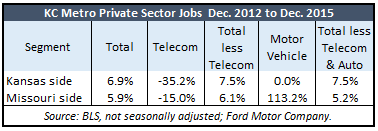

Similar analysis shows that the Kansas side of the Kansas City Metropolitan Area also grew faster than the Missouri side between December 2012 and December 2015. The Kansas side of the Metro grew by 6.9 percent compared to 5.9 percent in Missouri (i.e., jobs grew 17 percent faster in Kansas), but the Kansas advantage is even greater after considering two major anomalies that are unrelated to state tax policy. Telecommunications jobs were lost in both states, but the Sprint layoffs in Kansas had a much greater impact. The Kansas advantage widens to 23 percent (7.5 vs. 6.1) with this anomaly removed.

The Missouri side also benefitted from Ford adding 4,300 jobs to its Claycomo plant in response  to national demand for F-150 pickups and other vehicles.[i] The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a breakout for auto manufacturing at the state level but not for the Kansas City Metro, so it’s unknown if BLS has the accurate number of auto manufacturing jobs in their Metro market total. But if so, the Kansas advantage widens to 44 percent (7.5 vs. 5.2) when telecommunications and the Ford increase are removed. Total jobs less Telecom and Auto account for 99 percent of the Kansas side of the Metro and 98 percent of the Missouri side.

to national demand for F-150 pickups and other vehicles.[i] The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a breakout for auto manufacturing at the state level but not for the Kansas City Metro, so it’s unknown if BLS has the accurate number of auto manufacturing jobs in their Metro market total. But if so, the Kansas advantage widens to 44 percent (7.5 vs. 5.2) when telecommunications and the Ford increase are removed. Total jobs less Telecom and Auto account for 99 percent of the Kansas side of the Metro and 98 percent of the Missouri side.

FYI, recent media reports regarding Metro job comparisons included government jobs, made no consideration for the above anomalies and only covered a one-year period from February 2015 to February 2016.

To be clear, this is not presented as evidence that Kansas’ tax reform is ‘working.’ It will take several more years of data before extensive analysis can begin to fully comprehend the incremental benefits of Kansas having reduced income taxes. On the other hand, those claiming that tax reform isn’t working based on a simplistic average job growth that includes government are not basing their claim on sound economic analysis. That’s just politics.

[i] Confirmed by Ford Motor Company; employment went from 3,800 jobs at the end of 2012 to 8,100 at the end of 2015.