People and businesses that lose income during the COVID-19 shutdown will soon face another harsh reality – their property taxes are  coming due on May 10. Taxpayers need real relief that can only come from local government and educational institutions cutting their mill levies and reducing spending.

coming due on May 10. Taxpayers need real relief that can only come from local government and educational institutions cutting their mill levies and reducing spending.

History tells us that it won’t happen organically. During the 2009-10 recession, 83 of the states’ 105 counties increased their mill levy in 2009, and 2010 saw 71 increases. Commercial and industrial valuations declined slightly (2.6% and 4.3%, respectively), but residential values had a small net increase. New construction accounted for a 1.3% increase in 2009, while valuations of existing homes dipped 0.9% for a net increase of 0.4%. The net increase in 2010 of 0.1% resulted from a 1.3% gain from new construction and a 1.2% decline for existing homes.

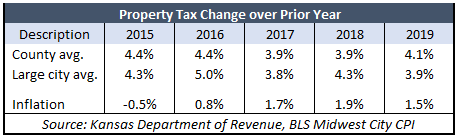

Cities and counties imposed property tax increases that are much higher than inflation over the years. County property  taxes due this year averaged 4.1%, and the 37 largest cities in Kansas averaged a 3.9% jump; inflation last year was just 1.5%. Keep in mind, counties increase taxes one year to be paid the next so that 4.1% will be paid this year but was “imposed” last year. Over the four previous years, property taxes increased between two and five times the rate of inflation.

taxes due this year averaged 4.1%, and the 37 largest cities in Kansas averaged a 3.9% jump; inflation last year was just 1.5%. Keep in mind, counties increase taxes one year to be paid the next so that 4.1% will be paid this year but was “imposed” last year. Over the four previous years, property taxes increased between two and five times the rate of inflation.

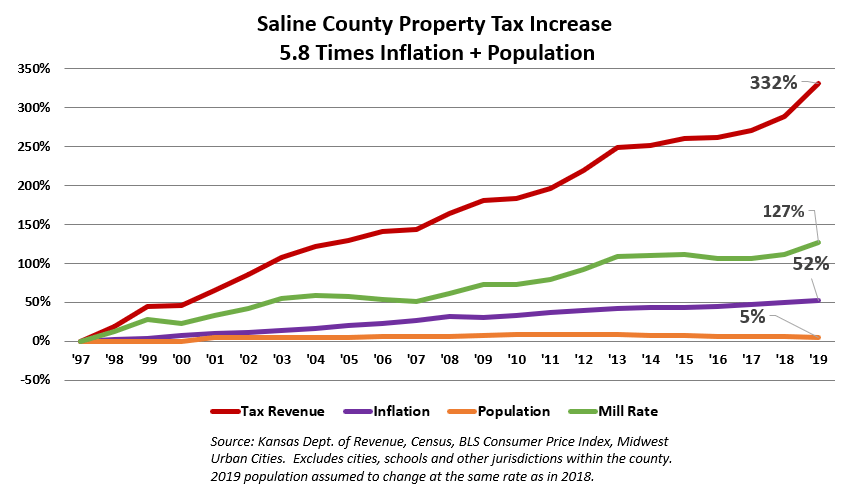

Even allowing for changes in population and inflation, property tax growth is breathtaking; 94 counties have imposed increases of more than double the combined rates of inflation and population.

Johnson County, with a 44% population gain since 1997 and inflation of 52%, increased property tax by 264%; that’s 2.7 times the combined rates of inflation and population.

It’s even worse in Saline County. Their 332% property tax hike is 5.8 times the combined rates of population (5%) and inflation. But that’s not even close to the worst example. Mitchell County officials’ 422% property tax increase is 10.7 times the combined rates of population (down 13%) and inflation. These charts are available for every county and large cities on KansasOpenGov.org.

Employers and homeowners need significant property tax relief, and local officials can do so if they’re willing to adjust spending (like the rest of us are doing). Here are just a few examples:

— Impose a hiring freeze and don’t replace employees who retire or resign. Schools and other local government entities in Kansas collectively have three times the national average of employees per capita, so there’s plenty of room to reduce staffing.

— Those with excess cash reserves should spend them. Johnson County, for example, projected to finish this year with $322.7 million in reserve. The COVID-19 impact could reduce reserves, but the county will still likely have room to cut.

— Consolidate duplicated functions across city and county lines. The management of Parks and Recreation is a good example. The Johnson County Parks and Recreation payroll is loaded with managers and directors, and so are cities like Olathe, Overland Park, and Lenexa. Overland Park has two directors collecting over $200,000.

— Examine the cost, effectiveness, and necessity of every program and function, and reduce costs accordingly. Outsourcing non-essential functions to the private sector (focusing on getting the same or better quality service at a better price) will also cut pension costs.

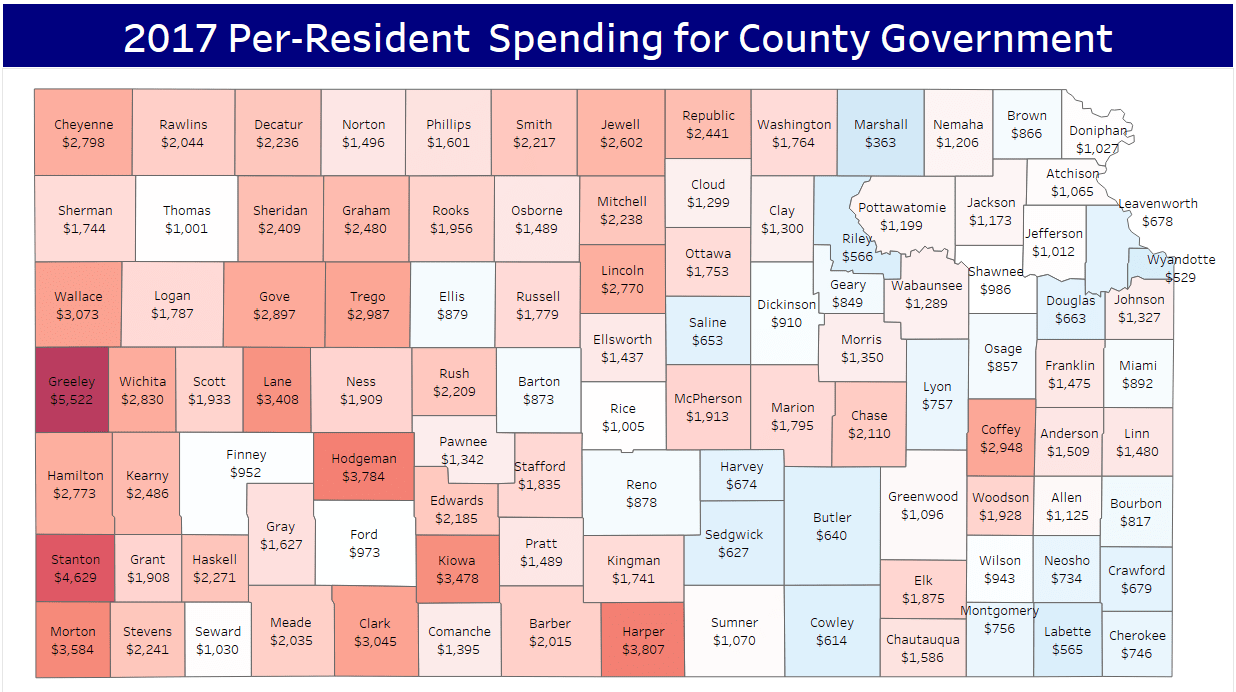

Michael Austin, director of our Center for Entrepreneurial Government, found enormous savings potential in his analysis of 2017 spending per resident among counties. Even among counties with a similar population, those spending the most per resident is three to four times as much as those spending the least.

State legislators can also help provide local property tax relief by passing Senate Bill 294 when they return to finish up the 2020 session. SB 294 eliminates the back-door property tax hikes from valuation increases by requiring local officials to vote on the entire amount of tax increase they impose. Each year, the mill rate is automatically reduced, so the new valuations produce the same dollar amount of property tax for the city or county. If officials want more tax revenue, they have to notify property owners in writing, specifying the amount of increase they propose and the date of a public ‘Truth in Taxation’ hearing where voters can share their concerns. Then, officials have to vote on the actual increase in property taxes.

State legislators can also help provide local property tax relief by passing Senate Bill 294 when they return to finish up the 2020 session. SB 294 eliminates the back-door property tax hikes from valuation increases by requiring local officials to vote on the entire amount of tax increase they impose. Each year, the mill rate is automatically reduced, so the new valuations produce the same dollar amount of property tax for the city or county. If officials want more tax revenue, they have to notify property owners in writing, specifying the amount of increase they propose and the date of a public ‘Truth in Taxation’ hearing where voters can share their concerns. Then, officials have to vote on the actual increase in property taxes.

The economic fallout from the COVID-19 shutdown will be enormous; some economists speculate the impact could be even worse than the 2009-10 recession. If history is any indication, government officials may engage in some minimal reductions so they can say they’re being responsive. What they’ll really be doing is asking citizens, reeling from a serious recession, to dig deeper so they don’t have to.