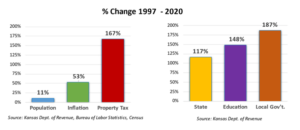

When you think of some of the highest taxes in the country, you don’t immediately think of Iola, Kansas. But, you should. According to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy’s research – highlighted in Kansas Policy Institute’s 2021 Green Book – a city the size of Iola had some of the highest effective tax rates on rural commercial property across the country. A property valued at $150,000 ranked 6th highest for property taxes compared to the same home in other states, while a property valued at $1 million with $200,000 in fixtures ranked 1st. These problems aren’t only facing rural areas: high property taxes in urban counties such as Wyandotte can push people out of their homes and lead to abandoned housing and evictions. The below infographic shows how property tax increased across Kansas relative to other factors since 1997.

The Lincoln Institute’s new report on property tax relief for homeowners has never been more relevant to Kansas. Policies on property tax relief can come from two angles: either limiting the growth of taxation, or providing new ways to reduce existing taxation. Governments have a tendency to expand over time, oftentimes creating new initiatives justified by the fact that the money exists to do them and not with any measurable goal identified at the start. Policies such as tax-and-expenditure limits help control the growth of both taxation and spending by tying them to measures such as inflation and population growth in the government’s jurisdiction. Kansas’ recently passed Truth in Taxation legislation is a significant step towards these policies. However, there is much work to be done with ensuring transparency in reporting from government bodies across the state. By next year, Truth in Taxation requires entities to mail their constituents if their rates are increasing. This process in the long run will save taxpayers millions of dollars in local and state taxes.

The people hit hardest by property taxes include senior citizens on fixed incomes (who already face obscenely high taxes because of Kansas’ policy towards different retirement plans), low-income households in gentrified neighborhoods, and people with sudden decreases in income – such as from a lost job. One solution is tax relief “circuit breakers,” which kick in when a household is “overloaded” by tax burdens. These policies use multiple-threshold formulas to calculate when taxes are exceeding income by an exorbitant amount and thus provide relief.

For instance, a circuit breaker with a 5% threshold compensates homeowners for any tax that exceeds 5% of their income. So, someone with an income of $20,000 and a tax bill of $1400 would receive a $400 tax credit since the bill exceeds 5% of their income ($1000). Kansas’ southern neighbor Oklahoma has a circuit breaker in the form of a refundable credit for people whose incomes are less than $12,000. Other states such as Maine offer upwards of $1,000 in credits with flexible caps on eligibility.

Many tax relief programs have ceilings on factors such as income. These ceilings should be set at the median household income to not exclude any families who could use the help. To avoid complex bureaucratic burdens, Kansas should avoid caps such as a net worth limit or residency requirements which make qualifying for tax relief more complicated and a greater cost to administration. Other small administrative tweaks such as allowing monthly payments of property taxes gives more flexibility to people to pay the same bills on time.

For all the relief that could exist for property tax, the best solution is controlling government spending and being transparent about increasing expenditures. Taxpayers’ interests and needs should decide how the government spends.